A Commentary on Philadelphia Arts and Artists, Minutiae, and Extraneum

"'Tis hard to say, if greater want of skill

Appear in writing or in judging ill;

But, of the two, less dang'rous is th'offence

To tire our patience, than mislead our sense."

--Alexander Pope

Right off the bat, I find myself wanting to point out what makes this essay superfluous. Native reasoning if not a mature sense of style should prevent this kind of sophomoric, self-effacing meta-text where confidence is required; so okay, I'm a crummy pitchman. It's like that ancient panel by Dave Berg in MAD magazine, where a slovenly teen, thrown out of the house to find summer employment, leans over the counter at the local supermarket and says to the manager,"Hey, man, you wouldn't be needing any help around here, right?" Smooth.

But here's the deal. Pope says that a misleading critic does more harm than a tiresome writer, and his Essay on Criticism names as the chief failing of critics the inability to differentiate between personal taste, a foible, and the eternal standards of divine Nature. I tell you straight out, nothing divine in origin wields me as its mortal instrument. All the voices in my head are accounted for. In this essay, I'm heeding an urge to introduce various arts and artists to a wider audience if I can and to champion a particular set of cultural values, but let me not make any pretense to the illuminating reason Alexander Pope believes in and describes. What I write, I freely admit, is less sense than sensibility.

The aesthetic one chooses accumulates as a reaction to innumerable clashes between an individual temperament and a particular environment. What it isn't is the culmination of human history or a binding prescription for how to make art. (No manifestos.) My sensibilities were forged in the 60s and thereafter. A lot of bumping around, then I finally decided to conduct my affairs based on empirical evidence only, and that's a good bit harder than it sounds. Requiring physical evidence as the basis of judgment excludes looking upon the things I am and what I do as aligned by fate; I would never attribute my individual tastes and inclinations to the unfolding of a divine will.

The only hagiography I practice includes various characters created by Hanna-Barbera, Bob Clampett, and the 1966 television Batman. Regular-old broadcast televison was such an influence on my way of looking at the world that I can hardly believe my daughter's experience is less formed by it. I ought to have known the primacy of the unblinking TV was temporary because I heard my parents reminisce about the age of radio. How could I not know what was coming? Modernity was so warm and blanketing while it lasted, I didn't realize the triumph of progress was nothing but a style, like the smoky, gray translucence of a plastic turntable cover or the green glow of stereo amps and receivers in the dark. Impressionist art reckoned with the technological innovation of photography and the Surrealists believed Freudian psychology would reveal the core of our experience. Similarly, I am an accident of my times; I understand the world in a particular way that is likely disposable, a consciousness batted around in some cosmic pinball machine for which replacement parts are no longer available.

How many artists remember to reckon the fine art to which they had access in their formative years a significant influence on their own aesthetic, and wasn't that a matter of happenstance and not destiny? Although I attended pubic grade schools when Delaware still offered art classes (another unique feature of my cohort), I got most of my training where Joseph Cornell and Francis Bacon got theirs, at the local museum. Giacometti claimed to have visited the Louvre about 5,000 times; my local was the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

I tell you, being near ground zero of Marcel Duchamp's influence on a century of artists and movements had a huge impact on me who have visited his shrine at the PMA at least twice a year since 1974. My collage work appropriates a ready-made river of print, and I often use a pseudo-documentary voice akin to Duchamp's notes for The Large Glass or Étant donnés and those amazing suitcases he did full of miniature versions of his entire ouevre. My Atlas features two mocking documentaries at once: its useless babble about how to make a relief collage and its reference to an ubiquitous advertisement in the comic books I devoured as a youth. My masks of Sherman and Peabody or Bazooka Joe and Mortimer are other works that realize secular icons of my 60s upbringing and stamp them with fine art credentials. Thanks, Marcel!

I'm nearly finished this disclaimer, which will permit me to write in this space about local artists whom I think worthy of the reader's attention. I won't need to remind anyone my own preferences are idiosyncratic and accounting for them requires much unpacking of circumstance and trivia. On the topic of the influence of randomness on sensibility, Giacometti, after his Surrealist period, spent ten or fifteen years sculpting tiny ancestors for the monumental "Walking" and "Standing" figures of the 50s. He started with a sizeable piece of material but would shave and refine until it was no bigger than a toothpick. He literally kept a year's production of sculptures in a matchbox. Then one day, Giacometti was crossing a Paris square and a horse-drawn carriage ran over his instep. The injury was serious enough he went to hospital, but did not remain to finish treatment.

The inexplicable result of this accident was that Giacometti was finally able to work in a larger scale. The inhibition that restrained him was somehow cured. We can't tell why; James Lord, Giacometti's biographer, relates the anecdote, but cannot explain the corresponding internal transformation. I put this out there as a sort of answer to those who will complain that my unwillingness to accept spiritual values as constants, or aesthetical manifestos as anything less than vulgar comedies precludes my own opinions from being worthwhile. On the contrary, the mysteries of human motivation are always profoundly interesting for the very reason that the mental processes of others are impossible to observe.

--12.2013

A NIGHT GALLERY-STYLE PORTRAIT of the ARTIST as a YOUNG MAN

WHY I'M NOT ON FACEBOOK ANY MORE

I learned today, 25 Jan. 2014, that an additive in my favorite soft drink has a dangerous side effect. As a result and to make the story short, I have to quarantine myself from Facebook posts for a period of 100 days. I can't take the chance I'll suddenly say something crucial in the middle of an FB post.

To be honest, I have a few cans of the old formula stashed away, for times when I need to boost the mind's eye; I'm keeping one to finish this essay, for instance, else I end up like Dr. McCoy staring at a knot of wires and connectors and the Helmet of Knowledge has worn off. Panax ginseng in large doses augments clarity of mind and offers new viewpoints on old problems and systems. What I intermittently envision through the fog and haze is a future where major improvements in technology will send the value of posts like this one soaring, a business model that isn't compatible with the social network in its current form.

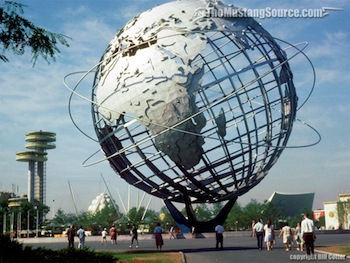

What a piece of business is man? Insisting on our individuality and asserting the right to privacy, we've always known our existence is meaningless (not to mention doomed) without incessant interaction between ourselves and other humans. That comfort we have listening to old-time space mission soundtracks, where an entity calling itself "Houston" and another "Apollo" engage in explorer/home-base dialogue, that feeling will be magnified, and every consciousness will feel connected to the entire "Unisphere." The values of the 1964 World's Fair at Flushing Meadows, New York, will finally be realized. Every boomer I know who grew up east of the Mississippi made a journey with his or her family to assert, "It's a Small World After All," (though I wouldn't want to pollute it!) at the Pepsi-Cola Pavillion,  a sentiment that has been playing ever since in Anaheim, California, until it became a source of annoyance to us, and then only because the promise went unfulfilled for nearly our lives entire.

a sentiment that has been playing ever since in Anaheim, California, until it became a source of annoyance to us, and then only because the promise went unfulfilled for nearly our lives entire.

For myself, shedding the cocoon of my youth and venturing out to join the congress of humans dates to a particular evening, when I was a seventeen-year-old, in a development southeast of the town of Newark, Delaware. I went into the neighborhood at night and enjoyed a strange prescience of mind: instead of receiving the lights and tree cover and individual, huddled tract houses as proof of the isolation of the families who lived there, I could "see" how flimsy the barrier truly was, how thin those walls and weak those porch lights. Our yards were only a quarter-acre wide and deep and the fences around them served to impede but not cut-off direct motion from my house to the Singer's place, kittywampus on the same backyard strip; these linked steel chains and pickets didn't establish a discrete domain of isolated Zimmerman, Crosley, Iezzi, and Shears. They indicated instead an already nostalgic skitterishness for the old days, like the momentary exuberances seen from shoulder level over a flock of sheep.

Another earlier memory of childhood: stepping into a crisp fall Monday morning to see if other pre-teens were at play in the common-to-all-of-us empty lot across Harmony Road, my boyhood address. I had the sudden realization that what I was going to report to the gang about last night's Ed Sullivan Show --Plate Spinners!-- was another common property to all. This was the meaning of television signals out of Philadelphia on one of six separate channels, and the strange dominance of a theater between 53rd and 54th streets on Broadway in New York City over a whole continent of synchronized viewers. A friend puts it this way: we may have been in separate frame houses (my neighbors and I shielded by asbestos-laden shingles, made of the toxic dust that forms cinder blocks), but we were each sitting on the same a priori "couch," word and abstraction. That moment contained the peaceful awareness of a shared attention between myself and twenty to thirty million souls, and an insight I think one doesn't have downloading a video from NetFlix or Amazon Prime.

--Plate Spinners!-- was another common property to all. This was the meaning of television signals out of Philadelphia on one of six separate channels, and the strange dominance of a theater between 53rd and 54th streets on Broadway in New York City over a whole continent of synchronized viewers. A friend puts it this way: we may have been in separate frame houses (my neighbors and I shielded by asbestos-laden shingles, made of the toxic dust that forms cinder blocks), but we were each sitting on the same a priori "couch," word and abstraction. That moment contained the peaceful awareness of a shared attention between myself and twenty to thirty million souls, and an insight I think one doesn't have downloading a video from NetFlix or Amazon Prime.

Just as a species can keep locked away in its genetic material a trait that is of little use coping with the environment at hand, I find myself with the gene for full disclosure in an age that rewards secret maneuverers and confidence men, in a country that has the most restrictive copywriting and licensing statutes on the planet. I am philosophical about being one of Elvis Costello's "[Men] out of time," since I know what is valued in one generation will soon be discarded, and that which is frivolous romanticism on Monday, may be essential nuts and bolts by the week-end.

With an impatient gesture I wave off the jeering, a suggestion my time is ill-spent, because I own the conviction that in the future, economics will reward the ability to account for one's own present with crisp, evocative prose and penetrating interpretations of that which one observes. Today, entertainment fictions are sprawling collaborations that require five to eight minutes to acknowlege in a crawl at the end. The future will want self-produced digital records of independent actors and their interactions with other, similarly equipped participants in a modish real; a maverick "journalist," to unearth a term with no present counterpart in our language, will command huge sums for self-recorded works spooled out over a single signature, or single signature style.

The future will want self-produced digital records of independent actors and their interactions with other, similarly equipped participants in a modish real; a maverick "journalist," to unearth a term with no present counterpart in our language, will command huge sums for self-recorded works spooled out over a single signature, or single signature style.

We have the seeds of this revolution all around us: gonzo journalism but with the hyper-subjectivity and paranoia of drug and alcohol abuse stripped away; so-called reality television that celebrates the acute and urbane, and not venality and shrill consumerism; anti-corporation practitioners in every art building public taste for an alternative to slogans and self-serving, capitalist bias. That uploaded video of the neighbor's naysaying cat plays to more people than all the digitized monstrosities in the latest, bloated cornpone from James Cameron. I'm saying my sooth on behalf of millions of free-agents posting reports from an evermore entangled and inter-dependent reality, men and women whose discipline and objectivity will be celebrated the same way we demand freakish partisanship in the present decade, to choose a word with just the right pedigree to convey life at this sprawling party.

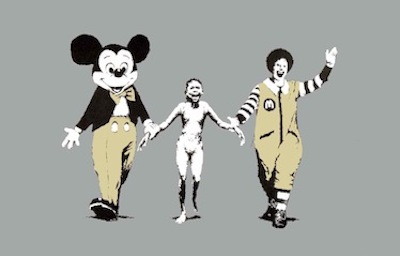

"Language is a scalpel, not a sledgehammer," is how I used to harangue my students. I credit today's right-wing media for its success at describing every liberal initiative in terms that make it seem anathema to the working man, their fun with words like "entitlement," "threat," "right-to-work," "Obamacare," "socialism," and "America." But I foresee an age-- maybe not by 2035 or even in this century, but it's coming-- when all things with a corporate reek will be disdained by the average man. Hard it is for me to believe the capitalist excesses of my time will go unpunished forever. As Rollerblade (1975) and Blade Runner (1982) became fulfilled prophecies in my lifetime, let my words be true for my children's children, and my children's children's children.

at describing every liberal initiative in terms that make it seem anathema to the working man, their fun with words like "entitlement," "threat," "right-to-work," "Obamacare," "socialism," and "America." But I foresee an age-- maybe not by 2035 or even in this century, but it's coming-- when all things with a corporate reek will be disdained by the average man. Hard it is for me to believe the capitalist excesses of my time will go unpunished forever. As Rollerblade (1975) and Blade Runner (1982) became fulfilled prophecies in my lifetime, let my words be true for my children's children, and my children's children's children.

Another reason besides "they suck" that will cause consumers to eventually resent and reject corporate media and embrace the mom and pop blockbuster is the exhaustion of the mass market, as we have already seen in the press, music, and video industries. Local business will gain power because computers and shipping revolutions will increase efficiency a hundredfold. Corporations have themselves to blame: they never rewarded the remaining essential workers when the second industrial revolution whittled the work force to a skilled few. They starved the middle class and shipwrecked the lower class by refusing to pay for the privilege of selling to and cheating Mr. Joe Six-Pack. They shrugged when the destruction of schools and government services entrenched class divides as never before. They refused to invest in the people and refused to make tax monies available to government so government could provide the investment of last resort.

In any case, I've got to step down from Facebook because of the visions of the future my Rockstar Diet Soda with panax ginseng, guarana, and taurine induces. In this future, we'll all be done with a banal corporate planet peopled by nothing but brand names and possessions. We'll want to lash together an Internet brimming with eyewitness accounts of adventures and field-level conditions. Joyfully we'll correlate data, an existential challenge that's at least impossible, at worst absurd. But that's why we drink so much caffeine.

Until then, I am, as ever, pleased to be your scamp,

Drew Zimmerman

Table of Contents:

Art Reviews--

- Art and Civics Dominate a Walking Tour of Philly's Downtown Sculptures

- In "Crafting Narratives" Show, Art is the Abstraction of Everyday Use

- Jim Strong: "Transcribing a Wilderness"

- Ralph Roether Expands Perspective in New Work

- Charles Burrus: Casting A Hot-Wax Tarot

- Nancy Kress, November, 2013, Muse Gallery show

- Show Has Arms-Length Scope but Broad Reach

- Susan McKee, January, 2014, Muse Gallery show

- Muse Gallery's 2013 Anniversary Group Show

- Considering "Last Days" with Pompeo

- Rashidah Salam: Using Art to Excavate Her Story

- Carolyn Harper Drapes a City's Invisibles in Brilliant Cloth

- Circle Gets the Square: Jim Kippen and Maureen Drdak

- Constance Culpepper: A Patterning Compulsion

- David Lynch at PAFA: Why a Duck

- Sara Bakken: Creative Force Made Real

- Bonnie Mettler: How Can There Be Any Sin in Sincere?

- Two Artists Interact at Muse Show

Essays--

- Pynchon Pins Shadows Against the Day

- Rejecting Liberal Kitsch in Art

- The Cook, the Thief, the Menu: A Brief

- What A Clockwork Orange Tells Us About Behaviorism

- 2020: The Year in Horror

- I Am the Man Who Invented Castaneda

- My 42 Years Reading The Recognitions

- Art Too Bruté

- The Abstracted Realist, A Disclaimer

- Why I Don't Worry About the Apocalypse

- Why I'm Not On Facebook Any More

- If You Don't Agree With Me...

- Loving Lady Ashley And Not Being an Ass About It

- The Lives_of_the_Saints

- You Don't Say

- Notes on The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor

- Self-Helpless

- Secrets of Blake's Marriage Revealed!

- Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood Stacks Competing Story Genres

Short Fiction

Animation (GIFs)--

- Night Gallery-Style

- Ad for The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor

- Citizen Kane Snow Dome

- Superman Transformation GIF!

- A Brief Re-Cap of the Winter of '14

- "Gateways to the Mind" Animation

- Amazing Hypno-Disc!

- Slinky Classic Toy

- Life is too short...

Cartoons--

- Free Concert Poster Download

- Apocrypha

- The Incredible Shrinking Man Comic

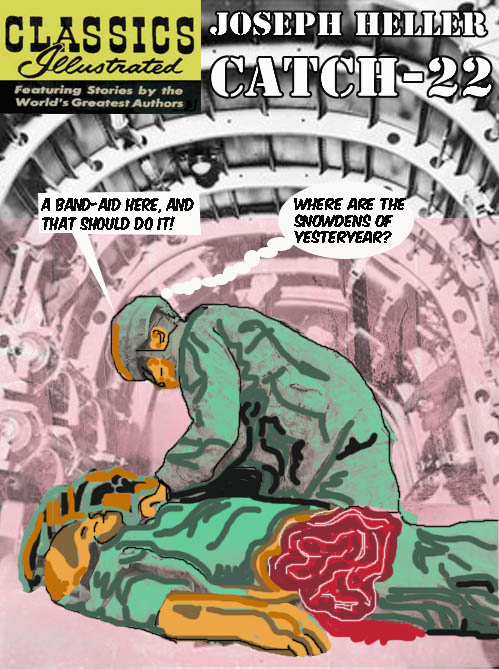

- Classics Illustrated: Catch-22

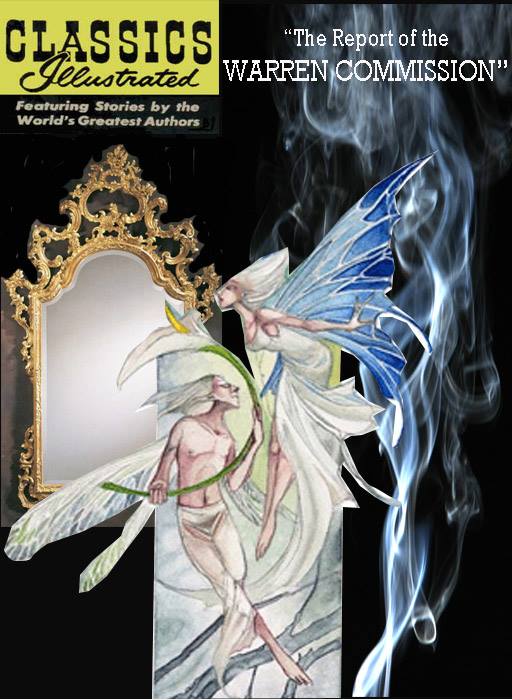

- Classics Illustrated: The Warren Commission Report

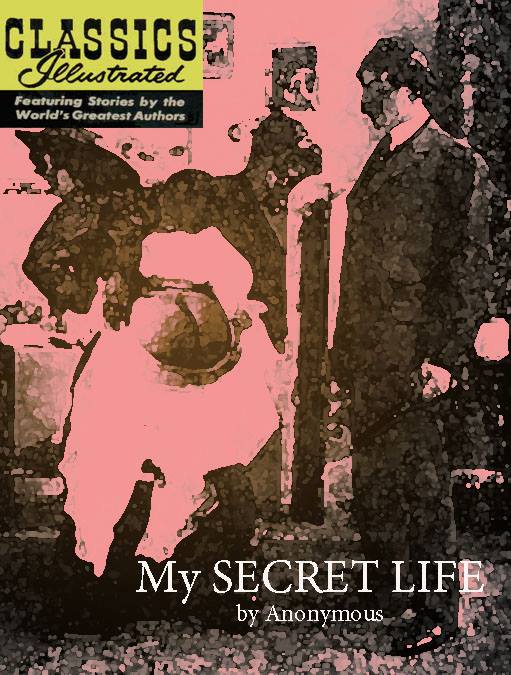

- Classics Illustrated: My Secret Life

- 2010-2021 Halloween Mask Comics

- Comic Strip Comics

- Follies Bér Comics

Satirical Flotsam--

- The Pepys T-Shirt Concession

- Samuel L. Jackson Jedi Knight Pen

- Save West Virginia --sung to the tune of "Country Roads, Take Me Home"

- COMING SOON!

- In A Flash, Abstract Sculpture Becomes Horrifically Real

- When Metaphors Go Wrong

- Mike Huckabee Sings about the Ladies

- The Four Stages of Human Consciousness

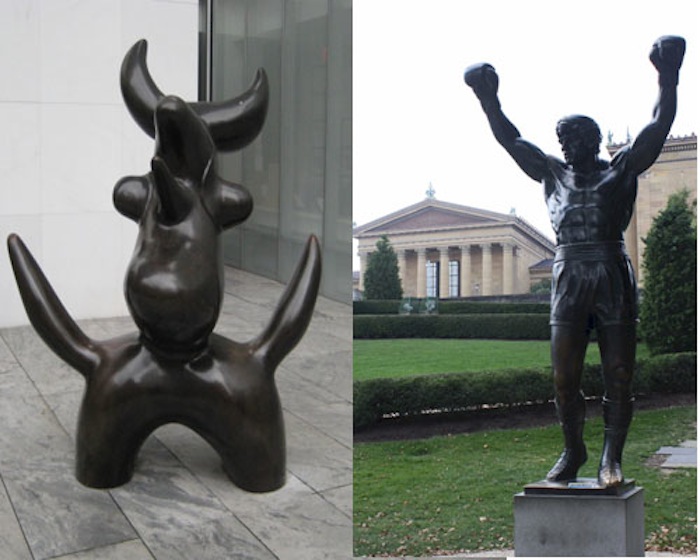

- The Rocky Statue

- A Baby's Arm Holding an Apple

- Drew's Quizzo; Win a Laptop Drive-In!

CITIZEN KANE SNOW DOME!

For years, "bronze people" (as they like to be called) have trudged to the top of the steps at the Philadelphia Museum of Art to imitate the triumphant pose of Joan Miro's Moonbird statue, famously located in the building's lobby.

A common impulse in all of art can probably be named, if one were arrogant enough to do so: to express in a medium other than time the stuff of experience. We are living, sensory organisms , bombarded with information and impression, and we have the skills to work a particular medium--words, paint, film, dirt, dance—to record what that experience was like. We exalt or condemn existence, maybe write a few postcards, describe or explain. Art happens.

It should go without saying there are different ways to accomplish art’s essential business, that artists go about the problem with different goals and different instruments, each according to their circumstance. My own experience of the world seems to be a compulsion to summarize and characterize what has happened to me verbally and to make pictures using paper and glue to illustrate the words in my head. The artist Charles Burrus, whose latest work is at Muse Gallery during July, 2014, explores experience as a landscape or starscape of light and color, without fussing too much over the verbiage or composing a narrative. Lately, he has produced fine pieces in encaustic, the medium of colored wax.

I have followed Charles Burrus’ work for several years, and “what the medium will do” is a matter of great importance to him. His curiosity is nearly scientific. He has made previously dense works in oil paint incorporating different kinds of paper and foil which were large-scale explorations of how much light can be emitted from a thick application of dark matter. His latest work in encaustic is much brighter, less abstract, and yields much more detail in a scaled-down space. The pleasure of physically working the wax and blending the pigments comes through in the gaiety of the colors, lusciousness of forms, and the sheer delight Mr. Burrus takes from achieving a compositional semblance of tropical fauna (Parrots) or a celestial swirl, and making that likeness in a foreign medium.

The recent encaustic paintings of Mr. Burrus often refer to a visual image, but his use of the materials delightfully and serendipitously abstracts the original. He is an artist who desires collaboration with chance because he believes that by letting go of conscious intent, a connection to the grand scheme of the universe will happen. It’s the same mystic impulse that justifies casting a spread of tarot cards to learn about some present person, or consulting star charts to coordinate what happens in the firmament with circumstances here below. In Galaxy Hub, Mr. Burrus literally imposes a bicycle sprocket on a nebulous gray swirl, expressing the central belief that informs all his work to this point: that there is a plan or mechanism unfolding in the seeming chaos of history. He has used bicycle parts in previous oils bearing titles referring to mythology. The particular reference is never very explicit; it conveys a general feeling that the cosmos conforms to a godly will compatible with human understanding.

or consulting star charts to coordinate what happens in the firmament with circumstances here below. In Galaxy Hub, Mr. Burrus literally imposes a bicycle sprocket on a nebulous gray swirl, expressing the central belief that informs all his work to this point: that there is a plan or mechanism unfolding in the seeming chaos of history. He has used bicycle parts in previous oils bearing titles referring to mythology. The particular reference is never very explicit; it conveys a general feeling that the cosmos conforms to a godly will compatible with human understanding.

Some of the most detailed and pictorial work in the current Muse Gallery show generates from images of the night sky. In A Wrinkle in Time, a man-made (or at least earthly) construction in triangular form with a swirling patchwork of colors is positioned in the foreground of a yellow and purple, glowing galaxy churning in the cosmically distant background. Or maybe it doesn’t! It doesn’t matter: the picture relates to a classic childhood book in which the vast loneliness of space is vanquished by human understanding. Similarly, Mr. Burrus exploring the physicality of wax and pigment squeezed through a heat gun to see what pictures alchemy creates expresses a faith that human consciousness can make something of what is essentially unsympathetic and inanimate matter.

The titles and associations in Mr. Burrus’ work are playful as opposed to being prescriptive, so I think he’s not trying to convey particular traits or characteristics in the pair of works entitled Thelma and Louise. On the other hand, the reference tells us something about what the artist is trying to get across. The pair are similar to one another compositionally, but the colors are different, creating the effect of a photo and its negative; thus, a generic pairing is established, but on the other hand he’s not saying the radiant masses hurtling through a field of colored daubs is Jack and Jill. The vivid image in the eponymous film was of a definitive burst of glory happening for the moment: a Big Bang moment, final, paradoxically deterministic, but creative and expressive, too. Thelma and Louise refused to accept a world where choice was limited, fate was fixed, and feeling was stifled, so they exploded like fireworks in the sky. It’s a lovely emblem for the spirit that Mr. Burrus conveys in his output of recent encaustics, a sensibility trained to the temporary fulfillment of light and energy and a refusal to bow to the darkness.

The titles and associations in Mr. Burrus’ work are playful as opposed to being prescriptive, so I think he’s not trying to convey particular traits or characteristics in the pair of works entitled Thelma and Louise. On the other hand, the reference tells us something about what the artist is trying to get across. The pair are similar to one another compositionally, but the colors are different, creating the effect of a photo and its negative; thus, a generic pairing is established, but on the other hand he’s not saying the radiant masses hurtling through a field of colored daubs is Jack and Jill. The vivid image in the eponymous film was of a definitive burst of glory happening for the moment: a Big Bang moment, final, paradoxically deterministic, but creative and expressive, too. Thelma and Louise refused to accept a world where choice was limited, fate was fixed, and feeling was stifled, so they exploded like fireworks in the sky. It’s a lovely emblem for the spirit that Mr. Burrus conveys in his output of recent encaustics, a sensibility trained to the temporary fulfillment of light and energy and a refusal to bow to the darkness.

In her November, 2013, Muse Gallery show, "Connected/Disconnect," Nancy Kress addressed ways we abstract ourselves from empirical reality. People in her work look into a distance that doesn't exist. They wear designer clothes, alluding to a fashion-world style consciousness beyond the frame of the picture. Ms. Kress employs different painting techniques to depict her subjects, indicating a mental process that sorts through the objective world and highlights or abstracts what it sees there according to very specific values and priorities.

The positions of the three women in the show's titular painting project different sorts of distraction: on a subway car, a woman applies make-up, another pulls an item from her purse, and a third is using a smart phone or some other adult busy box. The position of the women's legs conveys meaning. Without projecting a false depth, Ms. Kress attributes to her subjects a resting disconnection from the present subway car. Her skill at using body language to convey meaning reminds us that the eye perceives empirical data that can't easily be expressed in words.

Each lovely limb is synchronized with other limbs, creating a pattern that's similar to the bumpy rhythms of a train ride. Ms. Kress abstracts the window behind the seated figures, putting a glare of white on the lower third of the pane and dark polygons on the top. She places the three pretty females on their plastic blue bench with such precision, she doesn't need to fuss with the view through the window. The pattern of dangling limbs suggests the repetitious light of windows streaking past stationary facades.

Such pretty ladies. With a hand that invokes the sketchy graphics in fashion ads, Ms. Kress sexualizes her subjects. She details those lean, female bodies and composes a different chic "look" for each. The women's hair comes in all three colors of a magazine spread for L'Oreal. Dressed up and still working on their "look," the characters here are waiting to be seen but by whom? Great painting always contains a mystery, and here it's the inextricable puzzle of the gaze and its object.

Ms. Kress's equally spare but eloquent painting, Italian Cafe, induces the viewer to consider location choice as a component of a person's character.  It's an Italian cafe and all that signifies, with a wrought-iron bench outside and a brilliant live landscape in the background. (I reject the notion that the couple are indoors, sitting next to a cheesy mural, because of the blue light suffusing all and the painter's penchant for elegance.) The male figure stares blankly ahead at some dead abstraction with shoulders drooping. At least, he dresses nattily!

It's an Italian cafe and all that signifies, with a wrought-iron bench outside and a brilliant live landscape in the background. (I reject the notion that the couple are indoors, sitting next to a cheesy mural, because of the blue light suffusing all and the painter's penchant for elegance.) The male figure stares blankly ahead at some dead abstraction with shoulders drooping. At least, he dresses nattily!

The female in this two-person drama is more engaged with her surroundings if only because the blue of her turtleneck sweater harmonizes with the setting. Connected to the scene, she nevertheless distances herself from her companion by straightening her arm against her side and raising her right knee a couple of inches, suggesting a barricade. The man's jacket is a fleshy pastel and his face is an undetermined smear; he resembles a drooping penis. But the woman projects poise and fortitude, that Barbara Stanwyck vibe.

Ms. Kress uses a fine brushstroke to sketch outlines or suggest important details. She renders large spans of clothing, the flesh of the man's face, and the landscape with a knife. One technique brings out the dominant facts of the painting and the other suggests less articulated solids for which broad abstractions will suffice. Selective vision frames and details fashion cues in the woman's clothes, make-up, and hair, and generalizes the man's face and the picturesque Nature behind him. The picture uses composition and technique to present a disconnected couple from the woman's point of view.

In Cool Boots Nancy Kress again tells us how clothing represents the person wearing it and how the parts of our appearance that are skin-covered can be abstracted so long as the costume makes a statement.  A long-haired brunette wearing a western-style shirt and knee-high boots sits in the corner of a restaurant or bar. Although her outlines and the specific shaping of the boots are distinct, their color is blue or black. The chair she sits in is a luminous yellow-- it's Vincent's chair! Ms. Kress presents a human mystery lounging in some public place where people interact, but the space she occupies and the fetish boots she wears are more important than herself.

A long-haired brunette wearing a western-style shirt and knee-high boots sits in the corner of a restaurant or bar. Although her outlines and the specific shaping of the boots are distinct, their color is blue or black. The chair she sits in is a luminous yellow-- it's Vincent's chair! Ms. Kress presents a human mystery lounging in some public place where people interact, but the space she occupies and the fetish boots she wears are more important than herself.

Cool Boots is a simple painting but a gorgeous one. Ms. Kress uses her knife again and layers the blue paint like she's icing a cake. For the important objects in the composition, a paint brush applies contours and character. The duality of the technique, producing abstraction or specific detail, expresses Ms. Kress' meaning, that we often let styled objects convey our significance, whereas, our human selves might be disconnected from the projection.

In these three works from her show, Ms. Kress accurately represents what passes for discourse in the human present. Dialogue and ideas are irrelevant since all the backstory we really need can be expressed by a mere gesture, some style choices, and upscale props. What matters in the human experience is dressing well and being seen in the right places. The switch permitting interaction and communion is plainly in the "off" position.

PLEASE PATRONIZE OUR GREEDY AND CRIMINAL CORPORATE SPONSORS

TexEditing.com presents:

"About The Social Network , said Fincher,

'Words are just the way we lie to each other,'

Which doesn't seem to me that big a deal:

We only have words to say what we feel,

But after three months away from this site,

(Which, thank you, I managed w/o a fight),

I'm coming back, society of "Friends,"

The I-Use-Facebook-Too-Much guy, again,

With a story that came across my desk,

Written modestly by "Anonymous"

(Some nameless schlub or even one of you,

So 'share,' and I hope you will 'like' it, too)

And emailed to the web site I own

World Wide Web dot TexEditing dot com."

--Drew Zimmerman, March 2014

"Interactive wackiness ensues when a Main Line artist weds a Russian exotic dancer from Kensington, and they meet his father, a slightly mad Bell Laboratories bio-chemist. BOING! 'The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor' is an enjoyable Dr. Seuss for grown-ups.

PLUS, Feature 21: The reader moves from room to haunted room by entering passwords based on the 1966 Batman TV series. It is a sure bet someone will get around to selling those passwords, and I hear there's a James Bond trivia section, and another based on Beatles tunes as well!. ZOWIE!" --TexEditing.com

1472 Lines of Print/35 Pages of HTML!

Bonnie Mettler: "How Can There Be Any Sin in Sincere?"

During March, Muse Gallery hosted a show by the conspicuously talented Bonnie Mettler with two things going for it that are rare indeed in the smaller Philadelphia venues that feature less well known artists. She has superb skills with the paintbrush, and the content of her art is thematically challenging. One usually sees either painters whose topic is paint itself or deep thinkers with no regard for what technique signifies, so the combination of both of these in Mettler's show was a treat, indeed. I am going to point out one or two niggling

Mettler's brushwork reminds me of Cezanne. Everyone's brushwork, let's face it, would be better if it reminded us of Cezanne's, the use of complimentary colors to build dimension, eschewing tricks of perspective. To look closely at a single application of the paint in one spot is to actually feel the brush squeeze against the canvas to shed its load.

The compositions here are delightfully ambitious, not only because of the discipline required to indicate dimension and form exclusively with the contrast between light and dark pigment, but also because Ms. Mettler wants to distinguish between objects in the present and those that are ghosts from the relative past.

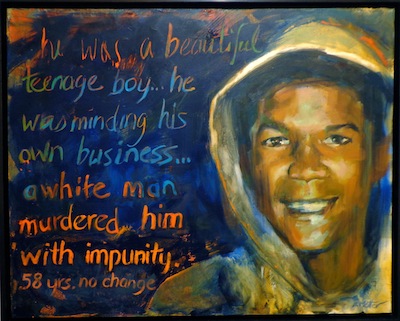

I have seen Bonnnie Mettler's portraiture before, but nothing so worthy of her splendid technique as the piece depicting Trayvon Martin as a beautiful adolescent wearing a hoodie. Because she is able to render the optimism of youth, its naivety and rambunctiousness, the portrait is immensely moving and the quotation immensely

As they used to say on What's My Line?, here's where I "Flip over all the cards," and unburden myself of my reservations about Bonnie Mettler's show, called My Racial Ignorance. I am an absolute bear when it comes to the urban legend, if you will, about parallel races of man, fighting it out for domination, trying to get their own, history-celebrating month, Citizens Park Blank Night, or excuse for bad manners. I simply don't recognize the so-called race difference between people whose skin is dark or not. No scientific evidence exists to credibly support the calumny of multiple races of humans exploiting nature on this planet, no more than science recognizes a species difference between a German shepherd and a Chihuahua. Excuse me, if they can breed, they're the same species, okay? Call this my racial ignorance if you will, but I refuse to wear the unnecessary baggage tag of "White," or accept membership in a group that other people demand I acknowledge as mines.

Ms. Mettler's show is a sincere lament over the ugly truth that huge segments of our democratic population have never heard of Emmet Till, his murder on account of the color of his skin by a damned, ignorant lynch mob, who kidnapped him in front of his own son because someone thought Emmett whistled at a white woman.

Bonnie Mettler is a jewel among painters and a fine person. I wish she could have packaged her brilliant paintings in less shabby sentiments.

"Ralph Roether Expands Perspective in New Work" published in ArtVoices Magazine, Winter 2015-16

The disposable nature of ideology and popular culture inhibits a reviewer of a work of art from appealing to universal rules when assessing its style or content. Our world isn’t monolithic; we piece it together collaboratively. One could blather, “I don’t like it,” and that’s okay, now we know how you feel, but we’re back on square one: a reality that makes sense only relatively speaking. Alternately, we have reason to be fascinated by the means of expression the artist chooses and the influences that shaped the contents of their thought: trapped in our own bleak subjectivity, evidence that other minds exist and struggle to find and communicate their experience as we do is encouraging.

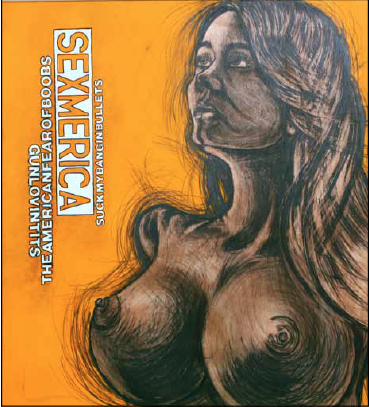

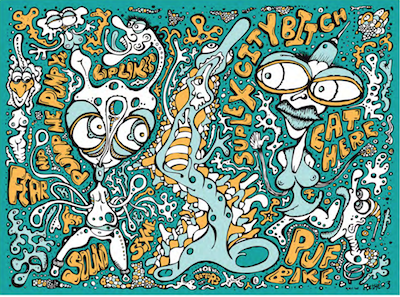

The recent work of Ralph Roether extends his usage of a cartoon style and explains how he got there, while adding a broader range of interest to the sex-obsessed content in his last wave of pictures. In correspondence with Artvoices, he cites R. Crumb, Ralph Bakshi, and John Kricfalusi as cartoonists whose work influences his own. The blatant eroticism in his Sexmerica series is reminiscent of the ribald subjects in Crumb and Bakshi, but his deft blending of provocative advertising-type copy (“gunlovintits” and “theAmericanfearofboobs”) with jiggly images uses those overripe breasts and bullet-like nipples to present an opinion not gorged with testosterone: America embraces gun culture but represses sexuality.

is reminiscent of the ribald subjects in Crumb and Bakshi, but his deft blending of provocative advertising-type copy (“gunlovintits” and “theAmericanfearofboobs”) with jiggly images uses those overripe breasts and bullet-like nipples to present an opinion not gorged with testosterone: America embraces gun culture but represses sexuality.

Roether warrants the influence on his paintings of Ren and Stimpy creator John Kricfalusi, whose hilarious animation of a dog and cat living together had an infantile pre-sexuality about them and a second-grader’s fascination with scatology. Roether’s Seahorsecock began as ink on paper and was converted digitally and colorized in Adobe Illustrator. Professing that the finished result comes from a technology-reliant process recalls the production studio where television cartoons are made. The art producer deconstructs biological entities into dislocated parts, bloodshot eyeballs, balloon-like breasts, and mindless penises. Kricfalusi’s work had the same post-rational metonymies writhing in an Apocalyptic background, with advertising and the sit-com form as its enervated setting. Who can forget, “It’s Log, it’s Log! It’s big, it’s heavy, it’s wood!”? Roether communicates the same Ren and Stimpy feeling that commercial slogans have replaced what previous generations accepted as real.

No exterior point of reference helps us to negotiate the world of commercial excesses clamoring for our attention or the billions of souls hoping to survive the final cut on American Idol. In a Nature that can only be understood subjectively, one last comfort is finding out the history that led to some other human sharing our space and sidling up to the trough. Roether rates Salvador Dali as an artist he admires,  but it hardly seems relevant to his work that Dali could melt watches or grow hair on a rock. The big, waxed mustache paired an academic mastery of oil paint with an intensely idiosyncratic vocabulary of forms. Skip the Freudian analysis. That giant hand certainly “represents” masturbation, but it’s Dali’s audacity in claiming space in the gallery for his feverishly personal vision that commands our attention.

but it hardly seems relevant to his work that Dali could melt watches or grow hair on a rock. The big, waxed mustache paired an academic mastery of oil paint with an intensely idiosyncratic vocabulary of forms. Skip the Freudian analysis. That giant hand certainly “represents” masturbation, but it’s Dali’s audacity in claiming space in the gallery for his feverishly personal vision that commands our attention.

Roether’s work relies for style on the graphic art of advertising and illustration, embracing commercial methods while expressing his highly individual obsessions, with pro wrestling, with typography, or with generous breasts. Experience throws new people arbitrarily into our individual consciousness on a daily basis. So much as the ceaseless accidents of existence make us anxious, taking the effort to map out how that artist or schoolyard shooter got that way re-establishes a sense of control. Roether’s self-portraits or portraits of children utilize an abstracted likeness, rendered with a cartoonish refinement of the crucial details plus a multi-layered white noise of random numbers and particular fonts.

Recognizing that Picasso and Jasper Johns used lettering as a subject reassures us that, yes by golly, Roether’s work, though it’s the damnedest thing, all those nekkid ladies and such, comes from a very long lineage. Setting such comforts aside, a thing about numerals and typography is that the individual signs, divorced from a larger context, lack correspondence to complete sentences. Be that as it may, every font communicates a mood that comes from the history of its use. Even when not used to fully form ideas they contain meaning. Roether’s use of numbers and letters as part of the composition refers to the endless, shrill pitch of advertising and how the deluge of claims on our attention, that incessant, hissing backdrop, eventually strips the signs from the products they represent.

Even when not used to fully form ideas they contain meaning. Roether’s use of numbers and letters as part of the composition refers to the endless, shrill pitch of advertising and how the deluge of claims on our attention, that incessant, hissing backdrop, eventually strips the signs from the products they represent.

The details about the physical means by which the images are produced are important. We long to see the process that leads from the man to the picture. His recent Blue Portrait series, self-portraits, and portraits of buxom Jenny Roether are painted on hollow-core doors. It’s a cheap material and one that might be salvaged in bulk from a home-remodeling site. Like Toulouse-Lautrec’s oils on cardboard, the thriftiness and accessibility of the surface matters, but the non-absorbency of the surface recommends it for the artist’s style of colorization and the ease with which transparency is achieved.

Roether writes that the documentary Crumb “opened my eyes to a whole other art world. [It] had a huge influence on me.” Terry Zwigoff’s film pleased many of us, perhaps because of Crumb’s candor about his own peculiar sexual obsessions and openness about the influence of his comic book-loving older brother, a fine artist who was mentally unfit to put his work before the public. Best of all, the movie has no less a critic than Robert Hughes to tell us that satirical cartoons exposing society’s underbelly are more than worthy of claims to high art. We benefit by recognizing that the over-the-top sensibilities of the satirist, looking in instead of out for some of his most extreme characterizations, have their origins in advertisements, pop culture, and between the matches at Wrestlemania.

Click on this link to return to Top of Page or Table of Contents.

"Coal is thieving, West Virginia!

Blue Ridge Mountains, stickin' it right in ya!

Time is long there, longer than Big Oil

Grabbing easy fortunes

Fracking streams and soil.

Take a look, country dudes,

At how coal has you screwed:

West Virginia, shitstorm's comin'

You've been had, country dudes!"

--sung to the tune of "Country Roads, Take Me Home"

Click on this link to go to Next Page, Top of Page or Table of Contents.

LOVING LADY ASHLEY AND NOT BEING AN ASS ABOUT IT

At left: Tyrone Power and Ava Gardner played Jake and Brett in the 1957 film of The Sun Also Rises

At left: Tyrone Power and Ava Gardner played Jake and Brett in the 1957 film of The Sun Also Rises

Several, non-sequential pages of The Sun Also Rises are given over to descriptions of Paris taxi rides. Jake takes a few and he enjoys telling the reader the order of the streets and the strings of shops and cafes on the route. Stripped of the significance they may have held for a very brief period in 1920, lists of place names that not only mean nothing to me, but also, I dare say, have no particular meaning to the average modern Parisian are like the Dada poem Gadji beri bimba by Hugo Ball and made into the song, “I Zimbra,” by Talking Heads. Minds wrecked by The Great War, Dadaists and Ball (who wrote their 1916 manifesto) intended to winnow the meaning from human speech, leaving only the fractured sounds of the poetical words. “With these sound poems we should renounce language, devastated and made impossible by journalism. We should withdraw into the innermost alchemy of the word…”

Dada rejected reason since it was with lying reason mankind had justified the pointless murder of millions across Europe. Journalism, Jake Barnes’ profession and the tool of opinion makers, was the deceptive practice of reporting empirical facts in such a way as to compel the reader to draw specific conclusions about them. We know from Ecclesiastes, however, that it is human vanity to impose meaning on the ineffable slaughter and feverish confusion of God’s creation. As narrator, Jake Barnes takes pains to present certain events that occurred over a six-month period without presuming to tell us what these events mean. Story itself, with its important causes and decisive battles, is a great vanity.

If Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises were a caper thriller featuring a bank heist, there’d be a scene where the thieves carefully dissect Robert Cohn’s self-pitying binge after Lady Ashley dumps him in San Sebastián. Cohn’s gloom clashes with the ritual pleasures of the Festival of San Fermin. Wherever Cohn and the other Americans settle themselves, a row erupts thanks to the impossibility of managing all the hurt feelings and strained friendships. Robert Cohn’s falling in love with Lady Brett Ashley creates an unmannerly interruption of a cheerful, but controlled routine, cultivated by Jake Barnes and his friends, to drunkenly celebrate the gift of life and the sad inevitability of death. Cohn’s hangdog, jilted-lover’s expression breaches an etiquette constructed to suppress unseemly displays of bitter emotion or other such effusion.

Jake’s narration wrestles with the journalistic impossibility of accurately and impartially communicating individual experience, a kind of immobilizing helplessness. Impotency sulks along his story’s Pyrenees spine. Cohn was emasculated by Lady Brett, Jake was unmanned by flying metal in WWI, and a whole, faithless generation of postwar expatriates was uprooted to Paris because “it may as well be Paris,” which is so good as any place to enact purposeless repetitions of photogenic taxi rides. Physically impotent from a ghastly war wound, Jake observes a code of detachment and resignation that doesn’t permit sulking or self-pity; alternately, Cohn makes his heartache obvious, goading others to notice and react. In Hemingway’s construction, drawing attention to one’s powerlessness is a passive-aggressive response to the efficacy of some other actor or a reaction to having been bested by them.The Dadaists enjoyed drawing words randomly from a hat and composing poems and art by that method. The game had one rule and it merely preserved the form of the contest; it didn’t espouse any other values: “play the cards you are dealt.”

Jake and Robert both have had a failed romance with Lady Brett, whose potency contrasts starkly with their own powerlessness. The Sun Also Rises values sexual prowess even as it diminishes the knack for arranging words in an attractive pattern. Jake disqualifies himself from having a romantic partnership with Brett because he physically cannot perform. How should he satisfy her? Lady Ashley is a celebrated beauty who attracts attention wherever she goes. Wined and dined by a Count in Paris, she is the subject of an impromptu fertility dance by a street troop in Pamplona. The matador throws his cape to her before defeating the bull, and, afterward, gives her the bloody trophy from the kill. Jake’s power is his stoicism and, maybe, his belief in the possibility of accurate journalism, but he lacks the virility to tame Brett’s sexuality.

Admittedly, Lady Ashley’s sexualty is a male construct, an interpretation of her beauty and vitality in terms of the male’s sexual desire for her. Much can be made of Hemingway’s arrangement of broken, emasculated men around a seductive, central figure of femininity. Equally grotesque in their impotence are the “bachelors” in Marcel Duchamp’s contemporary The Bride Stripped Bare (1915-1923). Male artists in the 20s expressed an anxiety about liberated women. Hemingway has Brett say how good it feels to be able to assert she hasn’t behaved like a bitch; bitchiness is indelibly a part of the male conception of a sexually liberated woman. If a reader confesses to being under Brett Ashley’s seductive spell, is he liable to the neuroses that created the fantasy? Because to admit it raises the issue of whether her admirers believe Brett devours her conquests, is it possible to be in love with Lady Ashley and not be an ass?

A reader always has the prerogative to evaluate the elements of a story as the artist presents them--pieces of the machinery of the given tale--and not in view of men’s oppression of women or some other political feature of the times in which the story was written. Lady Brett Ashley operates as a femme fatale in this story--of that there can be no doubt--and that her character may only be understood in terms of her sexuality certainly diminishes her as a fully realized woman; however, as the vivacious, doomed beauty who lost her true love in the war and has had a number of reckless and unwise brushes with men since, the character is a great success. She makes a convincing focus for a beehive of frustrated masculine desire constituting the central elements of the book’s plot. In a world in which all hope must be cast out, Brett is the consequence of desire. “Don’t be an ass!” is her admonition to anyone in her circle who gets on the verge of attaching importance to an inevitable and painful situation of which nothing may be done, anyway.

The wisdom of Ecclesiastes, which moral applies to the entire novel, accepts the will of God who set the sun in motion and empties the rivers into the sea. The problems of men are small and insignificant, occurring in opposition to reason. Jake Barnes doesn’t beat his chest over the effect of his war wound, and similarly, he doesn't decry the impossibility of his possessing Brett and her love. Stoic acceptance is the rule. Brett is a force of nature, inevitable and true. Jake suffers her seduction of Cohn and Romero. He endures her engagement to Mike. Yet, he is still Brett’s only resource when she is stranded in Madrid after releasing her matador conquest. The rule is it’s no use complaining when dealing with the consequences of natural law.

One may excise hope and accept the inevitable but still cultivate an aesthetic; the content is hopeless so at least let us put on a bit of style. For Barnes and Brett and good old Bill, behaving and being a good chap is the important thing. One doesn’t belabor unpleasantness. The obvious parallel is the romantic aesthetic of bullfighting of which Jake and Bill are passionate aficionados. The legendary matadors work very close to the bull, emblem of deadly power and virility. They don’t exaggerate the danger with any unnecessary movement, and they always show respect for the toro. Hemingway describes bullfighting and its mythologies in detail, inviting us to agree that the complex etiquette of the ring compares to the social rules and cues that attend friendships and love affairs. Ours is a heartbreaking reality, but let us not use that as an excuse to beat our brows and cast about for something to blame. Instead, let us cultivate dignity and honor, not because we have the right to them, but because we can by our own actions manifest them.

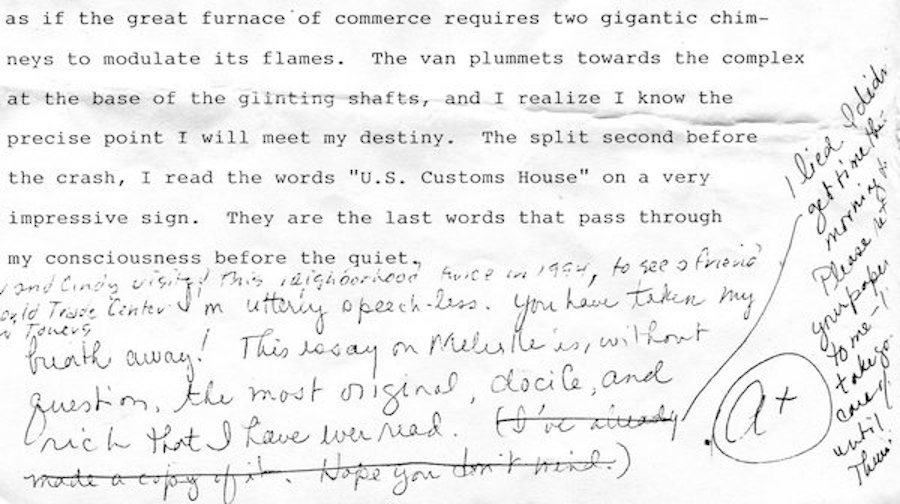

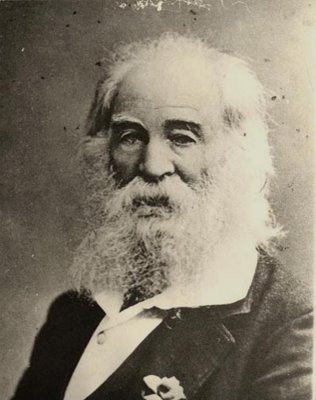

THE LIVES OF THE SAINTS

The following essay was written by me in 1994 while I was still a student at Temple University. Besides its brilliant defense of Herman Melville, customs clerk nonpareil, this piece contains a weird foreshadowing of a major catastrophe that befell the United States in the decade after its appearance. I have no explanation for it, and I am sure the reader will wonder with me at the essay's uncanny synchronicity with forces unseen.

I used to read Moby Dick on buses and subways going to and from a dreary job in a

video rental store. Besides brooding about vanity and implacable Fate, I often thought about

that Herman Melville, his twenty years as a customs agent. Surely, I knew more about the

author than I needed to read him, but I used to imagine the old salt found comfort in his

obscure clerkship after all those years of trying to hack it in the arts community. Melville was an

inspiration to me on endless, unvarying commutes, crammed elbow to elbow with barely

sentient humanity.

That Herman Melville rated himself some kind of hero is inconceivable. In fact, his is

a case where even the most admiring critic has difficulty reconciling the greatness of the

work with the mediocrity of the life. In The Creators, a pernicious , 800-page

Lives of the Saints for idolators of Art, Daniel J. Boorstin struggles to explain

Melville's audacious achievement. "[N]o Melvillian mystery is more tantalizing than how

and why he became a writer," Boorstin decides (Boorstin 645). "We might say that

Melville was an 'accidental' author, an inspired amateur. Or less charitably, that he

came to writing as an act of desperation-- for lack of anything better to do" (646).

That Herman Melville rated himself some kind of hero is inconceivable. In fact, his is

a case where even the most admiring critic has difficulty reconciling the greatness of the

work with the mediocrity of the life. In The Creators, a pernicious , 800-page

Lives of the Saints for idolators of Art, Daniel J. Boorstin struggles to explain

Melville's audacious achievement. "[N]o Melvillian mystery is more tantalizing than how

and why he became a writer," Boorstin decides (Boorstin 645). "We might say that

Melville was an 'accidental' author, an inspired amateur. Or less charitably, that he

came to writing as an act of desperation-- for lack of anything better to do" (646).

These absurdities are full of the crude assumption that one must become an author the way

one becomes a prophet, by answering an unmistakable voice whose origins are divine.

Melville wrote the archetypal American novel, but the impulse to do it was native to his

own frail circumstances, not the Heaven of artists in Boorstin's pantheon. Why invent a

category of mentalisms to account for an effect that can be explained empirically?

At the dirty street-level of subsistence, all behavior is commerce with the environment.

According to his opportunities, a man becomes sailor or mutineer, dinner for cannibals,

or a prisoner in the brig, a customs agent or the Toast of New York. By accident, one may

become the greatest novelist of the century or a footnote in an unfinished dissertation.

Nothing is served by the popular myth that writing is a sacred vocation.

Accident brings the author to the writing desk. It intrudes again when a reader tries to

deduce the man from his work. For instance, the Norton Anthology of American Literature

(1980) requires a few short stories and poems, all written after 1853, (the year

"Bartleby" was published and two years after Moby Dick), to stand for Melville's

entire achievement. Facts that are extraneous to Melville, the fire at his publisher's

warehouse that destroyed copies of his adventure stories and rare copies of "The Whale" or

the spatial limitations of textbooks and college surveys, become a major determinant in our

understanding of the man and his message. The Melville of the adventure novels and Moby

Dick is not the same author who writes "Bartleby, The Scrivener." Ishmael begins

Moby Dick expansively, with a global range of possibilities stretching away from

Nantucket, while the narrator of "Bartleby" assures us his remarks will be limited to a

puny fiefdom of copy clerks. It is sad to think a reader will pursue Melville in Norton's

anthologized edition, when the optimism of his embarkment had eroded to a fine dust.

At this point, I want to assure the reader that the essay unveils

the aforementioned eerie premonition of a national catastrophe shortly, and he or she will

be amazed and confused all in good time.

Additionally, I should break in on the essay to say the next page of the original, page three,

has sadly been lost, whether by an oversight at a copy machine or because I loaned it to a

sympathetic friend for feedback. I honestly don't remember. Be that as it may, I would

prefer not to produce a true bridge between the last sentence on page two and the first

sentence on page four; instead, I would remark that the missing section moves the essay

along to a direct critique of "Bartleby." I use the story to show how the Herman Melville

of his short fictions is no longer a young man trying to grasp the universe and the

potentially grand vistas and extraordinary adventures it contains. Instead, the author becomes a

kind of frontier Franz Kafka whose literary turf is existential man, desperately facing a

claustrophobic reality which is easier written about than observed. He has learned on the

instrument of slow torture in Kafka's "The Penal Colony," that everyday life is a cryptic

mix of metaphor and asphalt, concreteness (the empty icebox and the landlord pounding on

the door for his money) and incantation (for example, the invisible, restraining power of language

artifacts that define "old" money and "new" money in hide-bound, mid-19th century New York).

sympathetic friend for feedback. I honestly don't remember. Be that as it may, I would

prefer not to produce a true bridge between the last sentence on page two and the first

sentence on page four; instead, I would remark that the missing section moves the essay

along to a direct critique of "Bartleby." I use the story to show how the Herman Melville

of his short fictions is no longer a young man trying to grasp the universe and the

potentially grand vistas and extraordinary adventures it contains. Instead, the author becomes a

kind of frontier Franz Kafka whose literary turf is existential man, desperately facing a

claustrophobic reality which is easier written about than observed. He has learned on the

instrument of slow torture in Kafka's "The Penal Colony," that everyday life is a cryptic

mix of metaphor and asphalt, concreteness (the empty icebox and the landlord pounding on

the door for his money) and incantation (for example, the invisible, restraining power of language

artifacts that define "old" money and "new" money in hide-bound, mid-19th century New York).

[The manager of the office where Bartleby declines to do any work while

refusing to cease his embodiment of a working job title, lacks] the will to impose discipline on his

idiosyncratic staff. The improbable Turkey, who blots pages with ink and ginger cake, and

Nippers, who cannot sit comfortable at a desk, are completely incompatible with their

service, or at least half so. When Bartleby arrives, the worsening dysfunction of the

office soon earns the condemnation of other members of the legal brotherhood but does not

disturb the inertia of the weak-willed lawyer and supervisor. He will not replace his

clerks. Melville decribes the inevitable disintegration of purpose which accompanies

everyday friction with other beings. Humanity coexists awkwardly with the lofty roles

people aspire to play. We have at least job titles, even though no actual accomplishment

legitimizes those convenient labels. Perhaps Melville believed the office of "writer" is the

most shameful pretense of all. Like the narrative of the deedsmen, it projects itself

beyond the influence of critics, sentimentality, or fear while wearing the semblance of

immutable virtue.

The narrator's case shows the running down of the will from too much comfort,

"prudence" and "method" (Melville 636). In Bartleby, the will persists in such abundance

it is damned obstinacy. The gaunt clerk defies the very foundation of his post as Ahab

perverted his commission by choosing to contend with a single brute whale. The Law is a

pattern one must trace exactly. It binds the will. At first Bartleby refuses to repeat the

word with his voice, and inevitably he won't copy it with his pen. The will, what Bartleby

would prefer to do, is a ridiculous excess that leads to extinction. The image of

the would-be scribe disdaining to repeat what has already been written recalls the writer

who refuses to repeat the same adventure tales to please his audience. The nobility of

the gesture is immediately swallowed up by its absurdity: a silent writer contemplating a

blank wall is no writer at all, a paradox which Melville sums up completely in the

story's title.

The ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides considered action itself to be paradoxical

and, by extension, all plots and stories. Since the many are an indivisible whole, the

apparent diversity of objects and their movement hither and yon is impossible, an

illusion created in the imperfect human mind. "Bartleby, the Scrivener" expresses

Melville's adherence to classical metaphysics. He will not write a giddy popular fiction

full of novel happenings but only this claustrophilic thesis on the impossibility

of action and individuality.

The characters in "Bartleby" are truly compartments in a systematic whole. The continuity

of the narrator and the scribe is evident in the way Bartleby is never allowed to leave the law

office. "One prime thing is this--he was always there," the lawyer says, remarking on

Bartleby's "steadiness, his freedom from all dissipation...his great stillness" (649).

Experience disproves the assumption that Bartleby must venture out sometimes from the

walled-in darkness of the firm. In the Sunday episode and following Bartleby's "dismissal,"

the lawyer's attempts to find his office emptied of the cadaverous clerk are like a man's

conscious thoughts trying to sneak up on his own body. Every aspect of the lawyer and his

recording clerk seems to refer to a constant selfhood contained within a husk of sense.

The office partitions that prevent seeing but permit talk, the numerous walls throughout

the tale and the constant, unidentified narrative all suggest to me the persistent internal

monologue by which we identify ourselves, imprisoned in a corpse. Our bondage to this

phantom, though unconfirmed by the senses, is as permanent as the narrator's connection to

Bartleby, that is, until death:

Gradually I slid into the persuasion that these troubles of mine touching the scrivener had all been predestined from eternity, and Bartleby was billeted upon me for some mysterious purpose of an all-wise Providence, which it was not for a mere mortal like me to fathom. Yes, Bartleby stay there behind your screen, thought I; I shall persecute you no more; you are harmless and noiseless as any of these old chairs; in short, I never feel so private as when I know you are here. At last I feel it; I penetrate to the predestined purpose of my life. I am content. (662)

In the same way Melville presents a false twinning of the narrative consciousness and

Bartleby's pale cadaver, he creates a chimerical division of the physical functions

of the law office. The copyists and their employer fulfill the medieval prescription

of the humours. Red-faced Turkey is governed by an excess of blood that makes him sanguine;

Nipper is bilious, prone to indigestion and discontentment. Their employer embodies

drained out lethargy. Movement in such a system is impossible, and Melville's solipsistic

parable has all the drama of a body getting stiff. The illusion of plot in

"Bartleby" is a "diseased ambition" (639), like that which causes Nippers to grind his teeth

and grind the legs of his desk against the floor. The story gives a convincing display of

energy, tides of humours sloshing in a systematic frame, but it goes nowhere.

In Melville, we find the premature emergence of a fiction of entropy (not to mention,

in the chapters conveying encyclopedia abstracts to gloss the fiction, a post-modern

sensibility). The infinite possibilities of story are denied; fortune is replaced by

amputation and eventual paralysis. Melville's entire career conforms to the entropic path

of the sun that governs Turkey's ineffectiveness. South Seas heroics and sailor's yarns

carried their teller to a bright meridian followed by a long and slow decline. "What I feel

most moved to write," Melville complained, "that is banned--it will not pay" (Boorstin 652).

He persisted without an audience and produced a series of "dead letters," like those

short-falling missiles in "Bartleby"'s denoument."

Melville's fiction had no true precedent, and it alienated him from his own time.

In 70 years, some of his obsessions appear in Kafka. How similar to the scrivener's simple

"I would prefer not" is the fey revelation in "A Hunger Artist"? About his interminable

fasting, the artist admits "I couldn't find the food I liked" (Kafka 255). Kafka makes no

audience for a literature of declining possibilities, and the reception for Gaddis, Wallace,

and Pynchon since the 1950s is only a little better. Do we know what it was like to be

Melville in 1853, an anachronistic, metaphysical freak; a shrill Cassandra, borrowing to

live, depending on the depleted charity of anxious friends and family, eating grace,

refusing safety and routine like some crusty saint?

I do step into the car that beckons to me in the ______block of East 26th street, and the

bus jerks upwards, leaving Melville's old neighborhood. The object of Clarel's pilgrimage

remained obscure, obliterated by a scaffolded renovation.

Knocked about by my vehicle's sudden lift skyward, I sprawl on a bench. What I had been

searching for no longer matters. Below, rowhouses on Grammercy Park dissolve into jagged

blocks, and then, streets like black knife strokes on a rough, gray board receding

from view. The capsule has reached its apex. The engine sputters and dies. Falling

through miles of howling space, only one landmark stands plainly against the skyline----

a Colossus of Rhodes straddling the docks. For this destination, growing larger and larger

in the windshield panorama, we do not need an address. Human achievement visibly surges

towards it, as if the great furnace of commerce requires twin gigantic chimneys to modulate

its flames. The bus plummets towards the complex at the base of the towers' glinting shafts

and I realize I know the precise place I will meet my destiny. I read the words, "U.S.

Customs House," on a very impressive sign. They are the last words that pass through my

consciousness before [silence finally puts an end to all].