I Am the Man Who Invented Carlos Castaneda

Carlos Castaneda was the counter-culture phenomenon of the 70s who related his adventures on the edge of the human form. Under the tutelage of a Yaqui sorcerer with the absolutely generic name of don Juan, Castaneda, at one point in a long “apprenticeship to power,” evades the lattice of words and symbols that dictate the material world Man inhabits and joins other sentient beings in a different dimension than our own. One may have thought this would be a big deal, a guy escaping the chains of our reality, opening the doors of perception, taking it to a whole new level sort of thing, but I don’t recall Castaneda’s achievement causing much of a buzz. The Watergate hearings were on at the same time. That’s probably it.

Castaneda’s first book, A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, came to us on the newsstand claiming to be a California graduate school paper recounting an anthropological research project in the Sonoma desert of northern Mexico or southern Arizona. The actual whereabouts of Castaneda’s road to Ixtlan were unclear. The best explanation for the mystery is that Castaneda’s apprenticeship to don Juan Matus and his training to become a sorcerer didn’t literally happen; the whole story and twenty or so books and videos about exceeding the human form were a fiction devised by Carlos Castaneda, who died in 1998 (and if it could happen to him, it could happen to anyone).

Castaneda’s breakthrough transcendence of this earthly plane was fictional. Or was it?

My purpose in this essay is to acknowledge that Castaneda didn’t invent of whole cloth his psilocybin-induced insights into the constructed nature of human reality. I did! The honest truth is I am the man who invented Carlos Castaneda. It was I who invented the author of A Separate Reality and The Journey to Ixtlan. Superimposing my existence over another was easier than you might think. Unlike our empirical world, the textual universe has many available wormholes at the ready. Schematically, my accomplishment can be described as, “I said, ‘Carlos wrote, “Why are you always scribbling on that little pad,” don Juan laughed. “You look like you’re playing with yourself!”’” And so forth. Disclaimer: Don't try this at home! I'm a professional punctuator.

The anthropological treatise and its writer invented by me were obvious fakes, but my point in writing in the voice of Castaneda was to illustrate how the absence of empirical proof to support The Teachings of don Juan is literally immaterial. I’m not even the only writer who got in on the Carlos spoof. I was fascinated by Richard de Mille’s Castaneda's Journey: The Power and the Allegory (1976) that lays bare the falsehoods in the texts attributed to Castaneda without, of course, discerning my hand behind the scenes. Elsewhere, I remember an article in the L.A. Weekly (Jul 1998) in which Celeste Fremon claims she knew Carlos when he was a graduate student at UCLA and tosses around contradictory reports of his death in which “he left the world like don Juan with full awareness” seems as plausible as any. Reviewing The Art of Dreaming by one “Carlos Castaneda,” Vance Lehmkuhl in the Philadelphia City Paper (Sep 1993) makes an interesting point about the use of lucid dreaming to harness the fluidity of the dreamscape in our everyday, waking life. “Whatever kind of jerk he may be, and whether [Castaneda] stole his metaphysics from some old Mexican guy or synthesized it from various shamanistic and philosophical sources, Castaneda’s onto something.” I can’t recall the source exactly, but in another article concurrent with his death, the man who hurled himself from one side of a canyon to the other, suspending his luminous, egg-shaped form on tendrils of light, was described as “looking like a Mexican waiter.”

Carlos Castaneda didn’t have to be reporting real events to be relevant. If we realize the physical world we apprehend with our senses is constructed from cultural and evolutionary forces and not as it appears empirically, then any addition to the human narrative, especially mythic ones, substantially changes the narrative possibilities for every man’s existence. I think a consensus exists among anthropologists that the words a culture has to explain its history on Mother Earth are the limiting factor of the archetypes on which that culture survives. This is the tale of Carlos, who meets an old, wise guy in the desert, and the master teaches him how eliminating his interior dialogue is the first step to penetrating the illusions of everyday reality and finding the extra-dimensional realm in which our familiar universe is a mere subset. George Lucas: big fan.

Until now, the hallucinogenic nature of the sorcerer’s apprenticeship may have kept me from admitting I was the author of don Juan’s author. By this time, however, science has caught up to my vision, making a Castanedean model of reality more credible. Cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman of the University of California, for instance, asserts that the possibility of natural selection resulting in a human sensory apparatus that accurately perceives whatever is out there is exactly zero percent. Evolution is a life-promoting racket that only gives us enough equipment to manage our food and reproduce ourselves. We don't actually need to see things as they are. In the arena of theoretical physics, scientists assert that the universe exists in 16 or so dimensions. As in the classic, mathematical fable Flatland, we would perceive extra-dimensional beings intruding in our dimension as three-dimensional objects. We wouldn’t see them as they truly are. In don Juan’s desert encampments, simple, nearly devout actions performed on the mundane plane–like sweeping the brush and stones from the earth’s dusty carpet– have ramifications unseen in the realm of power, the Nagual. Science itself asserts the likelihood that this constructed reality of ours is not the whole drama.

The Castaneda books identify human consciousness as crucial to the self-deception about our true interaction with the galaxy. Rationality and the obsessive routines of consciousness I was taught in infancy construct a dependable reality in which to eat and procreate. Central to brushing these banalities aside is the skill of turning off the internal dialogue. That consciousness is the mysterious unifying force in reality makes intuitive sense when I consider the ineffable nature of thought. Nearly a hundred years into the Nuclear Age, 50 years since man landed on the moon, and two decades since the adoption of EZ Pass on the PA Turnpike, scientists still haven’t found biological structures in the brain to correspond with particular thoughts or memories; consciousness it seems is a non-mathematical, incalculable process spread all over the body. Our private acts of cognition aren’t even the command post for bodily activities or the center of our being. All that is an illusion. Writing for Frontiers in Psychology in November of 2017, David A. Oakley and Peter W. Halligan explain, "Despite the compelling subjective experience of executive self-control, we argue that 'consciousness' contains no top-down control processes and that 'consciousness' involves no executive, causal, or controlling relationship with any of the familiar psychological processes conventionally attributed to it."

Go figure. I knew that if I made perception of don Juan’s world dependent on turning off our interminable and inescapable internal dialogue then no one could say the key to that particular door of perception didn’t work. In the first place, who among us can freeze the endless prattle of the invisible mind, devoid of form or efficacy? (Nose Devoidoffunk? I did not invent George Clinton.) Second, we have no means of measuring anyone’s success at evading the banal traffic circles of the human consciousness. Unless, like, they can fly or something. If some guy can fly or something, me personally, I’d forget the question.

The primary teaching of A Yaqui Way of Knowledge is that the world of western civilization does not correspond to the world of nature, things as they really are. Our society clings to sad central myths, about limited resources and hegemonies of power. About the inferiority of our fellow homo sapiens. Somewhere in all those Castaneda books–ten of them rehashing and relearning from the same brief interaction between apprentice and sorcerer that occurred in the mid-sixties–”Carlos” tells how he and his group are going to perform the ultimate act signifying mastery of power: a jump into a canyon that would certainly be fatal to anyone who didn’t have supernatural abilities. A female sorceress confides to her cohort, “I’d have no problem taking the leap across the river so long as I knew my huaraches were waiting for me on the other side.” We are too used to the comfort of our depleted myths about human possibility to make radical changes in them.

A couple of pop philosophers I enjoy reading and listening to are that Slavoj žižek and, Mr. Fun, Jean Baudrillard. Their work begins with the assumption that myths and signs of culture transmit the culture unfailingly. Baudrillard pessimistically recounts the depletion of the human myth until our signs are no longer relevant to any present reality: they are copies of copies, faded, lacking clear outlines and no longer recognizable as what once was called “human.”  The don Juan series rejuvenates the hero’s journey, the mythic cure to what ails Baudrillard’s robotically androgyne, heroless modern culture. Placed in its proper category–a novel mimicking an anthropological treatise–we are invited to regard the Carlos Castaneda/don Juan cycle as a post-modern masterpiece, right up there with Jorge Luis Borges’ Labyrinths or the cross-country happening that was Ken Kesey and Neal Cassady’s 1964 Magic Bus Tour. In Borges’ “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” a staid reality is contaminated by a single volume of a much longer–but absent–encyclopedia, a reference guide to a reality strikingly similar to but fundamentally different than our own. Borges envisions the very casual way the virus of language invades and changes its host. In the postmodern sensibility, a strategic literary edit works as well as a major lifestyle reboot.

The don Juan series rejuvenates the hero’s journey, the mythic cure to what ails Baudrillard’s robotically androgyne, heroless modern culture. Placed in its proper category–a novel mimicking an anthropological treatise–we are invited to regard the Carlos Castaneda/don Juan cycle as a post-modern masterpiece, right up there with Jorge Luis Borges’ Labyrinths or the cross-country happening that was Ken Kesey and Neal Cassady’s 1964 Magic Bus Tour. In Borges’ “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” a staid reality is contaminated by a single volume of a much longer–but absent–encyclopedia, a reference guide to a reality strikingly similar to but fundamentally different than our own. Borges envisions the very casual way the virus of language invades and changes its host. In the postmodern sensibility, a strategic literary edit works as well as a major lifestyle reboot.

Years ago by now, I had this notion that it was appropriate to compare my invention of Carlos and don Juan to the opening in the fabric of reality that, to me, is Three Stooges comedy. I was never a fan of the Howard boys; I grew up in a violent family and grown men hitting each other with cooking utensils scared the bejeezus out of me. However, ever since I ran to the playground in my neighborhood to share their perceptions of 60s American culture with the ruffnecks and delinquents on my block, I’ve been amazed at how the ghastly, violent content of Moe, Larry, and Curly’s weird, sad, impoverished existence had been somehow normalized in kid conversation. Here was this deployment of the human form like had never been seen in history, and we were all ready to embrace absurdity for what is real. That thing that Curley did with his wrist and hands while going, “Woo-woo-woo”? What was that if not complete, unmeaning gibberish, and yet today, Curley’s pantomime is recognizable, understood by anyone. Nyuck! Why is there even a standard spelling for fucking nyuck?

I’m just a solitary artist trying to extract the meaning from my adventures in consciousness. Forgive me if I’ve succumbed to a persistent myth about the evolution of the species and the quest for mastery over a harsh environment. Alls I know is whatever’s going on, everything’s going on in it. My contribution to the collective myth of the human form is about deliberately exceeding our empirical reality. Radical uses of language expand narrative possibilities. The received story of man is about living a glorious life and then watching everything fall apart. We begin with an incandescent glow and end in dust and ruin. My pitch, if you will, is for a more complete story, at the level of eternity, where time and space don’t exist; they are mere artifacts of consciousness. Everything we are, have been, and will be is happening at the same instant, all at once. In my cosmology, we are never going to die and we’re already famous. As Dennis Hopper says to Christopher Walken’s don Vincenzo in True Romance, “If that's a fact, tell me: am I lying?”

June, 2022

My 42 Years Reading The Recognitions

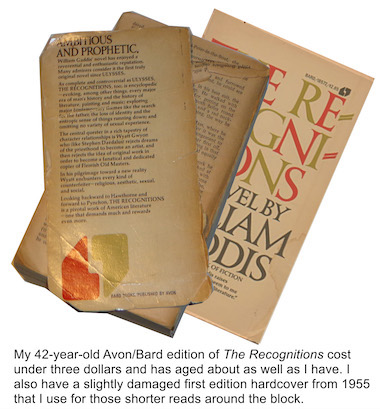

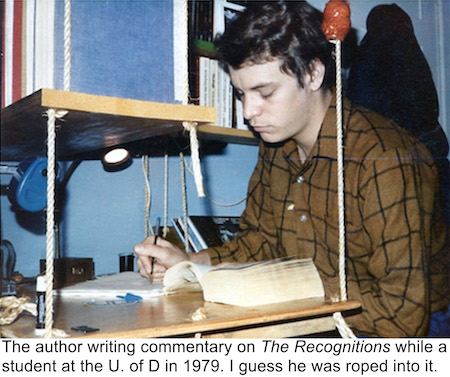

At the University of Delaware in 1979, my four years of dawdling as an English major were about to go “pffft.” Somewhere, I’m sure, a college transcript enshrines the lofty highs and leaden lows that marked my progress through about half of the courses necessary to frame a bachelor’s degree and taking twice the usual time to do it. Had I ever paid my student loans, I could actually buy a copy of that transcript today. Fanaticism (and a fair amount of alcohol)  distorted my focus in my first years as an adult. I had a notion that everything I needed to learn about writing and English had absolutely nothing to do with required courses in geography and French. My all-out commitment to literature and history courses was perfectly counterweighted by a complete indifference toward the assignments and tests of those superfluous “extra” classes.

distorted my focus in my first years as an adult. I had a notion that everything I needed to learn about writing and English had absolutely nothing to do with required courses in geography and French. My all-out commitment to literature and history courses was perfectly counterweighted by a complete indifference toward the assignments and tests of those superfluous “extra” classes.

I was practically a college dropout when I signed on to do a “special problem” in literature: one course/one semester, a sublimely refined schedule that appealed to my uncompromising lunacy. A professor of the modern novel admired my classwork and lively conversation on various absurdist writers and themes, and she put me up to what would be my last writing assignment before I left my hometown college altogether. Let me explain: in the 70s, hyper-qualified, published practitioners of practically any discipline were teaching in front of actual students at all but the flintiest institutions of learning. Today, those classes are conducted by graduate students who afford their tuition by disabusing freshmen and sophomores of the awkward notion that one may have a future in academics or the arts; however, in 1979, a genuine professor who had introduced me to John Barth, Donald Barthelme, and Edward Albee offered me three college credits to write a paper on William Gaddis’ monumental novel, The Recognitions. I guess I’ve been reading that book ever since.

In hindsight, that my first truly scholarly endeavor should be a close-reading of a 1000-page story about an everything-for-his-art ascetic who lets ordinary human relationships fall to pieces around him has a kind of inevitability. Wyatt Gwyon, the central figure in The Recognitions, possesses a superhuman facility with the tempera and religious temperament of 15th century Flemish masters, but he is prohibited by the Puritan faith of his forebears to make any original art: only God creates. With the kind of gooey, marzipan functionality by which a traditional novel resolves such dilemmas, Wyatt becomes an art forger of a very specific kind, exactly anticipating work by painters who were bound by the rules and practices of craft guilds, and whose every object on canvas was created to reflect the eye of the Almighty.

Nature is destiny, an inevitability not an opportunity. Whether from the necessities of the human form or the forms of fiction, postmodern literature often concludes that our physical being casts our fate, and free will is an amusing fantasy like dawdling over the possibility that our entire civilization rests on the head of a pin. The paper that I produced in my special problems in literature semester named the form of Gaddis’ novel as a predictor of its theme. The meaning a reader extracts from the text is conveyed less by individual actions of the characters than by author’s outrageously dense presentation of the New York arts scene after World War II. Most of the endless unraveling of the so-called plot takes place at various cocktail parties, attended by dozens of personalities whose participation in the life that art purports to represent is limited to maudlin outbursts of drink-fueled moroseness, fumbling the delivery of a new limerick that’s making the rounds, or a bitter, continuous gossip. The floating cast of regulars includes clinging women, dope addicts, and bitchy homosexuals. That’s bad, isn’t it? Maybe The Recognitions should be banned in advance, just in case high schools teach literature again.

Reading a novel that is as voluminous as some editions of the Holy Bible is like experiencing the endless, chattering dross of modern culture in real time. The comprehensive form of The Recognitions, I wrote, dramatizes the experience of time passing. Dawning in the reader’s mind is the realization that “story” itself is a quaint but silly vanity: outside the pages of a novel, nothing changes, almost nothing happens, and no one is redeemed.

Another feature of Gaddis’ epic form is the constant reminder that, despite material by the yard, characters in the novel are missing crucial information that could salvage their generally awful situations. A lattice of connections lays heavily over the story, yet the characters remain hopelessly in the dark about history essential to their own well being. Despite the omniscience wielded by so many narrators and experienced by absolutely no real person, ever, the author’s style is to not resolve missed opportunities and mistaken identities. The reader walks through a kind of maze, destined to overlook an egress in the same way that Otto, a kind of cheap imitation of Wyatt, wearing a fake arm sling and intending to meet his biological father for the first time, fails to realize that he’s taken a seat next to Frank Sinisterra, a forger looking to pass a bundle of queer bills. Frank Sinisterra, the real father of Chaby, the drug-dealing hood who is beating Otto’s time with poet, addict, and Gwyon model Esme! Frank Sinisterra, the fake ship’s doctor who killed Wyatt’s mother in a botched appendectomy, thus setting the whole concatenation in motion! In one regard, the novel’s title is ironic since its vastness and Gaddis’ stylistic reticence hide rather than illuminate likenesses.

Unlocking another set of associations for “recognitions'' describes my continuous study of Gaddis’ great American novel in the decades  since I followed Joseph R. Biden away from the campus of the University of Delaware. Determined that "Yes!" I could starve in more than one artistic discipline, by 1980 I had become a visual artist. In my first gallery appearance in 1981 on College Avenue in Newark, I showed a papiér mâché trout mask inspired by Captain Beefheart. To me, evidence of the hand of the artist is the primary attraction in a work of art. Appropriation was my metier: the reference to Don Van Vlient’s sound canvas masterpiece, Trout Mask Replica, was made with found paper, especially newsprint and advertising copy. In comparison, Wyatt Gwyon masters the tell-tale brushstrokes and compositional idiosyncrasies of classic painters who worked in a tradition that suppresses individual style. He produces entirely new work that masks his hand under the recognizable technique of another artist. With the right support from art criticism racketeers, these forgeries are promoted as hitherto unknown but recently discovered works by iconic masters.

since I followed Joseph R. Biden away from the campus of the University of Delaware. Determined that "Yes!" I could starve in more than one artistic discipline, by 1980 I had become a visual artist. In my first gallery appearance in 1981 on College Avenue in Newark, I showed a papiér mâché trout mask inspired by Captain Beefheart. To me, evidence of the hand of the artist is the primary attraction in a work of art. Appropriation was my metier: the reference to Don Van Vlient’s sound canvas masterpiece, Trout Mask Replica, was made with found paper, especially newsprint and advertising copy. In comparison, Wyatt Gwyon masters the tell-tale brushstrokes and compositional idiosyncrasies of classic painters who worked in a tradition that suppresses individual style. He produces entirely new work that masks his hand under the recognizable technique of another artist. With the right support from art criticism racketeers, these forgeries are promoted as hitherto unknown but recently discovered works by iconic masters.

No longer writing a college paper about Gaddis, I nevertheless read each of his books, identifying the signature concerns of his oeuvre, how the obsessive acquisition of money driving JR’s titular character is not “the root of all evil,” but rather what happens when the game of investing and extracting capital becomes an end and not a means. The elementary school bizwiz is truly just a kid, turning bupkis into higher-priced bupkis because “that’s what you do.” JR earned its author a National Book Award. Reading A Frolic of His Own, I learned how the technology that produced key punch cards and was essential to the computer revolution was stolen from the player piano industry. I even got an autographed copy of Gaddis’ Carpenter’s Gothic because a friend of mine used to produce an arts interview program for the BBC. Along with its idiosyncratic punctuation of human speech, the author’s work has distinctive themes, especially these two: the power of scholarship, knowing the origins of the linguistic fossils and artifacts among which we live; and the likelihood that one has missed or forgotten something essential.

Gaddis’ use of dialogue became for me an entryway to a deeper understanding of his account of the temporal landscape. Like James Joyce, Gaddis eschews the standard punctuation of dialogue, especially quotation marks: words said aloud are introduced with an em dash and never conventionally attributed to a speaker. Joyce’s great contribution to literature was his characterization of internal dialogue, the free-associating ghost in the machine that most of us connect to our genuine, secret selves. Gaddis likely admired Joyce’s presentation of a particular moment in time as containing the whole history of language, but my understanding is he rejected any suggestion that internal dialogue might be identified with our true nature or soul.

Strikingly, nowhere in The Recognitions does the reader learn the words or phrases a character is thinking. The book conveys the facial expressions of a man in deep thought (“He had the look of someone who had just taken a bite of fish and found it full of bones.”) but acknowledges no interiority. Consistent with the radical behaviorism of Skinner and his followers, Gaddis rejects the homespun notion that internal dialogue is the origin of any empirically measurable activity. Language in the private consciousness reacts to stimuli but doesn’t formulate the actions of the physical body or will an action into being. In my lifetime, for example, I have successfully given up drinking. Hell, I’ve done it more than once! If I’ve learned anything about addiction, it’s that telling yourself to end a dependency is all but pointless. When relief comes, the transformation is in the body, not the mind. The best advice you can give an addict is to ignore your self-serving, lying consciousness completely, like Ulysses putting wax in his ears.

Consciousness is where rationalization takes place, not determination, the true source of which is in the sinew and tissue collecting the scars of our battles and beatdowns. Most of us are barely in touch with the history of positive and negative consequences that, in effect, form our destiny. We translate what the body knows into language, and at best it’s a clumsy correspondence. If you don’t believe me, observe for yourself what happens when you recognize a face, a somewhere-in-the-flesh process for which any cognitive, verbal description is completely superfluous.

I have argued elsewhere that William Gaddis’ reputation as one of the first postmodern writers may likely be attributed to his ultimately gibberish presentation of dialogue in The Recognitions. About half of the book unspools as hilarious/horrific cocktail party banter, celebrating a guest who doesn’t show, toasting a host no one knows, and honking without communicating in the same circle one gaggled with at the last party and the one before that. In a traditional novel, dialogue advances the plot and reveals the nature or interior life of characters. Like the chatter constantly streaming between my ears, the conversation in Gaddis provides little more than background noise consisting of fragments of jokes, allusions to the work of unidentified artists and writers, and descriptions of places and events that get crucial facts wrong. Postmodernism ultimately describes an existence where objective facts hang in the air like a license plate collection nailed to the barn wall. Once these signs had meaning; they represented something. Now, they are the wrapping that the old values and abstractions came in, meaningless but an entertaining and absorbing use of a blank wall.

Forms of story or art, existing in the absence of necessity, characterize what we oxy-moronically call “postmodernism.” Consider that the necessity of a painting by Hugo Van der Goes in the 15th century was to capture a likeness of a particular model in a very specific space and time. The artist mixes colors, poses the model, and applies paint to canvas with the single-minded intention of capturing an objectively understood image, recognizable to consumers of the painting and to God Himself. Modernism in fiction (Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner) and painting (Picasso, de Kooning, O’Keeffe) supplants God with spirituality and extends the categories of an acceptable subject to include the subjective life of the mind, but meaning is still possible. The artist marshals her talent to represent a verifiable “other,” recognizable to all. After modernism, the forms of expression continue as always but they no longer stand for an objective or even a necessarily intelligible reality. Accident replaces necessity; thus Max, Gaddis’ successful painter/author, hangs an actual worker’s paint-stained shirt in a frame, and nobody knows what it is, but they know what they like.

When I write that consciousness is not formative of behavior, the reader ought to realize I am not diminishing the power of words. I love the logical structures one builds with sounds and syntax. That they make poor descriptions of the biological imperatives of my life (such as it is) is not to say that they do not possess admirable qualities as a thing apart from the...cosmos. I struggle to choose a final word in the last sentence that isn’t contaminated by “the life of the mind,” something truly outside the language structures we compulsively inhabit. Postmodernism teaches us the discipline of acknowledging symbols are not the thing they represent. Despising abstractions because they aren’t “real,” well, you get extra credit for that; it isn’t part of the assignment.

The visual arts have long come to terms with the elementary observation that an artist represents a subject, and that the representation pleases the eye– or pleases the mind– apart from the absolutely incontrovertible fact that handiwork, whether by Wyeth or Warhol, is not the thing itself. My wife likes to tell the story of a time we visited the Barnes Museum when it was still in Lower Merion on Latches Key Lane. In one of those galleries where some of the West’s greatest art works are displayed with all the care a 12-year-old gives to tacking a magazine photo of Justin Bieber over the bed, a woman commented on an Henri Rousseau representation of a tiger in a jungle. She knew that Rousseau is considered a “primitive,” but I think she hadn’t given much thought to what that label actually signifies.

“You can see,” she said to her companion, full of her own erudition, “that it doesn’t look like a tiger.”

“Well, no,” I muttered, perhaps out of their hearing–-I’m never sure. “For one thing, Rousseau’s tiger is flat.”

Postmodernism disciplines the effete esthetes among us against the error of demanding verisimilitude as a pre-condition for art. Language approximates rather poorly our experience of being alive; making a picture of a subject doesn’t recreate the experience of having the original at hand. Even so, these games we play to try to communicate to others our individual interactions with nature are intrinsically interesting. We enjoy how the artist moves the pieces around. In Joyce or Gaddis– or Henri Rousseau, for that matter– style is the subject, not some impossible construct purporting to be “how things really are.” That I’ve learned by reading The Recognitions what is necessary to sustain oneself in the material world is unlikely, yet its erudition, satire, and representation of the fragility of experience occupy an esteemed position in my mental life. What useful advice has John Lennon ever given me, “All you need is love”?

I could say Gaddis’ novel, by the example of the travails of its central character, encourages me to move forward in my own art and career, which I’d have to admit is a career only in the sense that I’m constantly working at it. I like that Wyatt Gwyon rejects the sensible expectations of his heritage, inheriting his father’s ministry. He does what he must do artistically. Can producing a likeness of his dead mother compensate the child for her absence? Despite denying the nature of his forebears, Wyatt never resolves the guilt he feels for breaking with Puritan tradition. He imitates the style of Flemish painters whose rectitude and adherence to received forms is compatible with the Puritanism he was supposed to have left behind.

The Recognitions completely trashes the notion that business and art are compatible. The advertising executive whom Esther lives with when Wyatt does what Wyatt must do finds her ex’s copy of The Lives of the Saints and is thrilled with the prospect of turning it into a commercial entertainment, no doubt with the abortion pill for which his agency has the account as a sponsor. The dealer who profits from Wyatt’s forgeries is one Recktall Brown, represented as having a stark likeness to a pig. He is the kind who repackages a two cents per gallon cleaning fluid in six-ounce bottles and charges a thousand percent mark-up. Gaddis’ outline of the man is nearly as allegorical as John Bunyan characters with names like “Pilgrim” and “Hypocrisy.”

Once Wyatt’s work commands impossible sums of that ill begotten money, the unused cash piles up in his squalid studio. I thought about Alberto Giacometti, whose heyday was during the time period about which Gaddis writes. The greatest known sculptor of the twentieth century lived in a one-room studio shack, hidden in a Paris alley. He and his long-suffering wife slept in a loft above the filthy workspace. Late in his career, Giacometti literally had stacks of cash under the bed and no plumbing whatsoever.

The sales apparatus for original art tramples on the integrity of the artist and the cultural contribution of his or her work. We should not, therefore, equate being unknown and unsold with being untalented. Early in his career, Wyatt has completed several original canvases and is readying them for a show. A critic offers to write a favorable review in exchange for cash, and Wyatt predictably declines. The canvases remain obscure and unseen until eventually they are destroyed in a fire, an outcome consistent with Fate’s decree that Wyatt must remain anonymous. Another player in the art community, Basil Valentine is the art expert Recktall Brown enlists to provide the historical credentials for his protege’s imitations of Flemish masters. Valentine's successful hoodwink of the art experts confirms to himself his superiority over less privileged and less cultivated men. Of what use is Wyatt's integrity entangled with such vipers as these?

In the end, Gaddis’ most extensive criticism of the commercial art world comes across in the conversational fragments of which I have spoken, the overheard chatter of writers, reviewers, agents, and advertising men that unequivocally destroys all hope that the artist will be understood by the general public, so full it is of grotesque distortions, sloganeering, and lowbrow pandering. For the most part, Gaddis’ animosity towards critics anticipated their reaction to his book. While The Recognitions has been called the next great American novel after Moby Dick in recent years, it was not initially acclaimed, and its stylistic individuality was the primary cause of the negative critical response. Of course, seventy years passed between the publication of Melville’s masterpiece and when it finally received an enlightened academic assessment.

Early on in my 42 years of reading and rereading William Gaddis’ The Recognitions, I believed the author meant to condemn everything modern and secular. The comparison between Wyatt’s attention to detail and knowledge of his materials to the Abstract Expressionists celebrated in the 1951 cover story for Life magazine seemed prejudiced towards the religious rigor of the former. A rumor propagated at one of the Manhattan parties claims inherent vice of modern paint will cause the colors to decompose within a generation and these new fellows don't seem to care. Alternatively, the description of the guild-approved Flemish painters in the 1400s who made pleasing the eye of God their goal simply reeks of quality and spiritual edification. Despite these comparisons, a particular incident occuring near the start of the novel shows Gaddis’ lack of prejudice against modern art or the individual vision that is its defining characteristic.

Wyatt visits an uptown gallery to see Picasso’s roughly 7- by 11-foot Night Fishing at Antibes (1939, apparently the MoMA has it now) and is absolutely transfixed by the painting, calling the experience a recognition of illuminated truth that might happen to someone only seven times in a lifetime. Picasso creates a primal scene of a fisherman’s attempt to violently overcome a swimming fish and feed his family. A large-breasted girl with a bicycle and an ice cream cone stands on the pier awaiting the outcome. Not monochromatic like Guernica from the same period, Night Fishing uses a palette of luminous colors, with especially liquid pools of blue and aqua. The representational style, however, is similar to the expression of violence and outrage in Picasso’s account of the bombing of a Basque village, and indeed, as Picasso finished the work, the Germans invaded Poland. Gaddis’ uses that particular piece, an expression of Picasso’s anxiety over the start of WWII and a reference to the historical periods in his own artistic output, to indicate the kind of artist Wyatt Gwyon could have been had not the combination of cruel happenstance and cold destiny intervened.

Picasso among all modern artists epitomizes the combination of an almost divine creativity and a personal mythology. The rarity of Wyatt’s rapture indicates how precious are the moments when the imperatives of life are laid bare by an artist’s ingenuity. Liberated from mundane nature (having to earn a living) and liberated from conventional ways of seeing, the artist with the means and damned obstinance to express a singular vision is greatly blessed, and equally rich is the public that recognizes the creator living anonymously among them.

--Drew Zimmerman, 02-14-2022

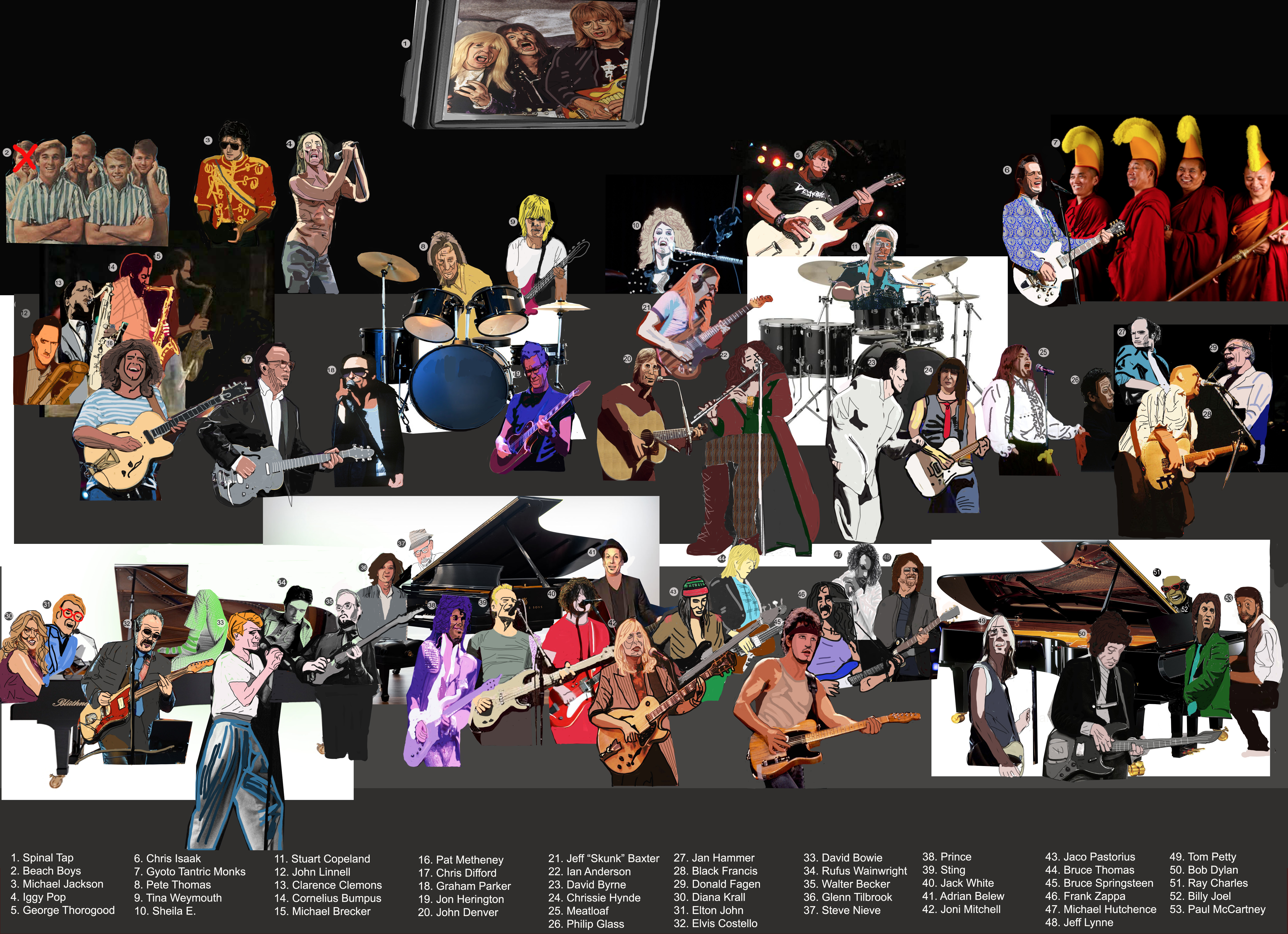

Dude: A Free Poster of the Most Memorable Performers I've Seen in Concert, from

John Denver (1974) to Steely Dan/Elvis Costello (2015)

Art Too Bruté

In my five decades of tracking down artwork in museums and galleries, the most moving exhibition I ever saw wasn’t one I was expecting to induce tears. On other trips, I journeyed to Chicago to see Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte; I made it to the MoMA before Guernica was returned to Spain; I saw pieces of the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens and in the British Museum in London. Seeing icons of the canon of Western Art in person deeply satisfies, and inevitably the visitor finds elements of scale or color or context no mere photograph conveys, but the time tears streamed down my face in the presence of art wasn’t one of those times I was mentally comparing the actual work to a colored plate in a monograph.

Outsider artist and novelist Henry Darger (1892-1973) amassed a 15,145-page work bound in fifteen volumes, with three of them consisting of several hundred illustrations of his subject, the Vivien Girls and their adventures in the Realm of the Unreal.

The most moving exhibition I ever saw was at New York’s American Folk Museum in 2003, The Perfect Game: America Looks at Baseball. The collection presented works by renowned, “outsider” artists like Thornton Dial and Elijah Pierce, but mostly they were created by unidentified baseball fans. Particularly affecting for me were anonymous representations of baseball stadiums crafted by prison inmates, like the whimsy bottle containing a tiny Maryland State Penitentiary, composed of painted and carved wood slivers, with a ballfield in its courtyard. Baseball as a theme appealed to me because I love that game and the Americana it represents; additionally, I recognized the compulsion of the artists to record their experience as fans, and a clear view of the mental environment of the creator vividly recommended these painstakingly amassed, eensy-weensy cathedrals of sport.

A whole category of art comes into existence to materially connect the artist to an absent subject. Craft restores a treasured person, thing, or idea abandoned in the past or else physically unavailable in the artist’s present. The material nature of the created object matters much more than does the presence of a painting or sculpture in an art museum. Whether because it conveys specific ideas and aesthetics rather than a visceral presence or because it is so readily available in secondhand sources, Modern Art especially may be understood a priori. After all, Guernica is known much more than it is experienced. One must go to Spain to literally see it, and even should you make the trip, the El Reina gallery has long lines of hot and crabby tourists, and wouldn’t it be more fun and more memorable on a pricey vacation to Madrid to sample the cocido madrileño at a local cafe? Picasso’s masterpiece is available-- except for its scale-- in printed reproductions and voluminous commentaries; the private artist building a model of a ballfield in a bottle does so to create a specifically physical presence to compensate for the absence of that which only exists in memory.

Proposing his own radical art aesthetic, Jean Dubuffet infamously championed what he called “Art Brut,” which was work created free from the influence of formal academies or commercial galleries. Art produced by shut-ins, inmates, and the clinically insane is truer to the human impulse to create a material presence than the work produced by rigorously trained captives of the mainstream, whose work is mediated by establishment culture. Preferring Art Brut to “the art of museums, galleries, salons,” Dubuffet disparages the “cultural art” associated with professional intellectuals whose instinctive capacity for creating or appreciating art has been worn out like the seat of their pants from sitting too long in the lecture hall (Glimcher, 101) . Cultural art merely rearranges certain accepted ideas in public circulation, and never comes near to the primal “clairvoyance” by which organic, authentic art is hewn from the dross of experience.

Click on this link to go to Next Page, Top of Page or Table of Contents.

Please Support Our Criminally Negligent Corporate Sponsors

Why I Don’t Worry About The Apocalypse, And You Shouldn’t Either

Some of my friends seem certain that the Apocalypse is happening or about to. They anxiously post photos of lonely, frail castaways standing at the edge of a precipice. They paint studies for The Four Horses or angels in mid-fall, grappling in pitched battle. They’re drunk like Francis Ford Copolla on the overwhelming evidence of a world gone mad; the struggle is “Now!” and the terror is real, but, you know, the ending is a mess. (Of the movie version, Playboy wrote, “When it is good, it is very, very good, and when it is bad, it’s Brando.”)

Every age of mankind is peopled with disheveled prophets predicting the end of times. Ours is nothing new. “The sense of an ending,” Frank Kermode wrote in 1967, pervades the stories we tell, hard-wired into the syntax of human speech, an indelible story grammar dictating how justice will be administered according to the magnitude of countless crimes and sins. Before we could literally destroy life on Earth, mankind believed that divine retribution stood ready in the sky, to mete out death to every unrepentant sinner and tee times with Billy Graham in Elysian Fields for the faithful and virtuous. The empirical exercise of tallying the many evils that gravely vex mortal man devolves into irrational hallucinations of fire and brimstone. The Book of Revelations and 50s science fiction torture the brain with chimerical visions: beasts with a thousand eyes, alien invaders, giant tarantulas marching from Los Alamos, the maw of a flaming lion filled with stars, the paws that refreshes.

I don’t pay no never mind to visions of a grandiose doom that settles all scores for two reasons. The first of these consoles me that the god of vengeance and wrath is a human concoction. I consider it a human vanity to ascribe the flaws of men’s nature to the lord of the universe. Does the secret spark that produced the cosmos and its indecipherable mysteries compile a wrinkled enemies list, and lie in wait in an angry froth to obliterate the names written upon it? That description applies to Donald J. Trump and not the divinity. The god who punishes, who gives a fig about affronts to his majesty, the god of the Old Testament is a creature of tribal yearnings for justice, and it is human vanity to attribute our anxieties to our maker.

Such a flawed and wrathful monster with his flaming sword, his comets, his rampages in Downtown Tokyo was vainly produced in the imagination of men and has nothing to do with the cosmic order. In ancient texts, Plato describes this demiurge; furthermore, the poet William Blake ridicules the false god Nobodaddy, “the farting, belching ‘Father of Jealousy’ who hides himself in clouds and loves ‘hanging & drawing & quartering / Every bit as well as war & slaughtering.’” Man’s vanity is to conceive of God as possessing mankind’s aggression and spitefulness, and all is vanity. We put our faith in material things and institutions that we cannot sustain, and we crave an omniscient deity who shares our blind passions and petty obsessions. On the contrary. Ecclesiastes teaches us that creation exists in an infinite space and time that surpasses the human scale and, perhaps, human understanding. Generations come and generations go. The rivers flow into the sea and yet it never fills. That which has been will be.

I wouldn’t lie and tell you I don’t brood about the tragic present my generation has lived to endure, this cruel slap in the face against everything we expected of government, nature, and everyday life. The disintegration of the democracy I held so dear and thought would never in America fade away destroys happiness and warps my fellow-feeling. The rapidity of global warming, hundred-degree temperatures recorded above the Arctic Circle for the first time, a Greenland that is truly green, and the encroachment of the ocean on the lowlands overwhelm me. In my dreams I am a polar bear, piteously overdressed for a surprise summer, searching in vain for food on ice flows that no longer exist. I mourn the displacement of science and empirical fact by conspiracy theories and Twitter feeds produced by computer-generated bots originating in dark cabals dedicated to lies and divisiveness. Plus, Plague(!), made much worse by the medieval forces described above. The feudal Dark Ages, about which I smugly laughed in my naive and privileged youth, has yet returned with a vengeance in my lifetime. Yes, I grieve for my country.

Like my friends, I am amazed and aghast that our life has come to this (and it’s only going to get worse), but I restrain myself from thinking I am a witness to Apocalypse. The forces that overwhelm us do not have a divine cause and our sad lot is not retribution for sin. The kind of justice we are experiencing has physical causes and tragic effects that science and an understanding of the selfishness and vanity of human behavior readily explain.

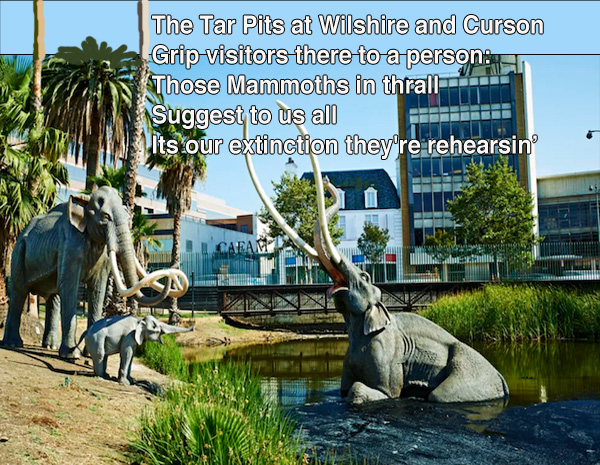

We like to romanticize the fall of Mayan civilization, and so recently as June 2020, the Daily Express reported their stone calendar predicting the end of times was still relevant. The last popularly reported expiration date for the planet had been miscalculated, and here we go again. Despite mythologizing the Mayan’s insider information about the will of the Cosmos, we certainly have reason to be attentive to Mayan history. A jungle-based civilization of 8,500,000 people, they were wiped out, not by a catastrophic bolt from the blue, but by a combination of unforeseen climatic anomalies, a failing infrastructure, and a degeneration of faith in their leaders and basic societal bonds. It could happen to anyone.

This brings me to the other reason I don’t brood about a coming Apocalypse. The lesson of the failure of Mayan civilization is not that man is subject to divine retribution for his sins and that our only hope is repentance and bloody human sacrifice. Rather, they teach us that our problems are of the physical world and reflective of the weakness of our communities. Let’s face it: the cosmos is dedicated to the propagation of life and experience. Our human vanity is that existence has been ordered for our sake alone. All life is interconnected and every molecule participates in the conscious perpetuation of the cosmic “drama” if you will. In this eternally unfolding story, human civilization means scarcely more than the reign of Tyrannosaurus Rex or a colony of novel coronavirus.

Instead of waiting for the comet that finally obliterates us or joining some cult of Godzilla, remember that violation of physical law and our failure to constantly attend the highest principles of a free society--especially concern for the basic dignity of every citizen--are what brought us to this precipice to begin with. Don’t just jump into space and expect God to redeem you. I ask myself, was I kind and charitable to my fellow man? Did I separate my plastic and aluminum, and provide for a public infrastructure to promote composting? Do I vote thoughtfully in every election, including the niggling little ones for judges and members of the school board? Before I as an individual can abdicate my responsibility to preserve individual freedom in cooperation with the physical world, I should ask, “Have I done everything I could to advance the species?” The lone known survivor of a suicidal leap from the Golden Gate Bridge gives his testimony on YouTube. Despairing deeply, believing himself at the last, he took his leap, and a millisecond later a thought occurred to him, “What if I counted my straws wrong?”

--Drew Zimmerman, June 2020

In “Crafting Narratives” Show, Art is the Abstraction of Everyday Use

In a 1956 interview on NBC-TV, Marcel Duchamp describes the dramatic moment his work as a conventional artist changed course irrevocably. He had been painting in the manner of Impressionism because it was the official style of the only fine arts education available during Duchamp’s youth. By the end of the first decade of the 1900s, Duchamp determined that he wouldn’t paint any longer blindly following immediate public taste; he would, from then on, paint only what pleased and interested himself. To reinforce the notion, he got a day job in a library so as not to be dependent on painting to earn his daily bread.

The first work produced by the newly liberated artist made a chocolate grinder its subject, thereby elevating a craft implement to a position of art. Duchamp tells James Johnson Sweeney, director of the Guggenheim Museum, that he became delighted by the motif of a chocolate grinder when he came upon an actual mechanical one in a chocolatier’s window. It was critical that the machine had been pulled out of its useful place in the mass production of candy and put before the public as the emblem of the chocolate shop’s virtue. The repurposing of the industrial machine was visually logical in the era that was experimenting with Cubism and abstraction. The cluster of metallic drums spawned by the necessities of the grinding process had the unexpected characteristic of being aesthetically pleasing. Also, Duchamp was amused by the verbal and visual sexual punning suggested by the device.

that he became delighted by the motif of a chocolate grinder when he came upon an actual mechanical one in a chocolatier’s window. It was critical that the machine had been pulled out of its useful place in the mass production of candy and put before the public as the emblem of the chocolate shop’s virtue. The repurposing of the industrial machine was visually logical in the era that was experimenting with Cubism and abstraction. The cluster of metallic drums spawned by the necessities of the grinding process had the unexpected characteristic of being aesthetically pleasing. Also, Duchamp was amused by the verbal and visual sexual punning suggested by the device.

He would paint the chocolate grinder’s form twice in what he describes as a “mechanical” style, and later deploy it as a dysfunctional reproductive organ in the mixed media The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass). The artist recognized that industrial processes, born of pure practicality, created independent of artistic intention a kind of “ready-made” art, abstract sculptures with a pleasing form divorced from their chocolate-grinding, bottle-drying, bird-caging, or excretory functions. At the start of the Twentieth Century, Duchamp embraced the industrialization of common life as being in harmony with the long processes of history, rather than subject to the short-lived whims of popular taste. Wanting to be an artist of his time, he tells Sweeney, Duchamp utilized the mechanical style of rendering three dimensions and incorporated mass-produced forms in his creations.

The impulse to take everyday materials associated with practical work and use them to make works of art is central to the show "Crafting Narratives," on display in Philadelphia’s Art in City Hall space until New Year’s Eve, 2019. Shaving distinctions between craft and art is a parlor-room pastime of dubious value; however, art is the logical successor to craft whatever else we attempt to say about it. Metalworking, paper-making, weaving, painting, pottery--all craft traditions begin as the manufacture of practical goods for everyday purposes. Using that same accumulated knowledge of the material and the forms into which it can be worked, artists break with craft tradition by creating objects that have no value as furniture, arrowheads, boxes, blankets, or other tools. Instead, art un-empirically consoles the human psyche, most basically as a means of commemorating human events, personal and public.

on display in Philadelphia’s Art in City Hall space until New Year’s Eve, 2019. Shaving distinctions between craft and art is a parlor-room pastime of dubious value; however, art is the logical successor to craft whatever else we attempt to say about it. Metalworking, paper-making, weaving, painting, pottery--all craft traditions begin as the manufacture of practical goods for everyday purposes. Using that same accumulated knowledge of the material and the forms into which it can be worked, artists break with craft tradition by creating objects that have no value as furniture, arrowheads, boxes, blankets, or other tools. Instead, art un-empirically consoles the human psyche, most basically as a means of commemorating human events, personal and public.

The subject of making aids to memory characterizes metalsmith Patricia Sullivan’s Portrait of Woman in Twelve-sided Frame, Sullivan enshrines tiny photographs of a woman and her environs in lockets of metalwork, a classic form, so old as photography or locks of hair. In her blog, she acknowledges another subject at play here is the dimensional similarity between lockets and the digital widgets that distinguish our accounts on social media, those tiny photos that if you click on them, link the face of the person contributing to a discourse with their biographical information and full history. Conceived as a precursor of the digital emblem that makes identity also a brand, Sullivan’s lockets depart from craft itself and think artfully about what constitutes a memory and what solace we might seek from it.

Beyond the practicality of chains and chambers is the immaterial pleasure of safeguarding an image of the beloved, and beyond that Sullivan finds a second level of abstraction. Portrait of Woman in Twelve-Sided Frame metacognitively explores what a portrait is for, while shrinking from objectifying more than an abstraction of a particular woman. Carefully preserved pictures include a lady obscured behind her hair and hand, and a nondescript rowhouse of routine red brick. Unless one already possesses intimate knowledge of the person and place in the photographs, they reveal very little, but a practical portrait is beside the point: like Duchamp’s ready-mades, Sullivan’s Portrait defines a border between manufactured products and the mysterious subset of craft we call “art.”

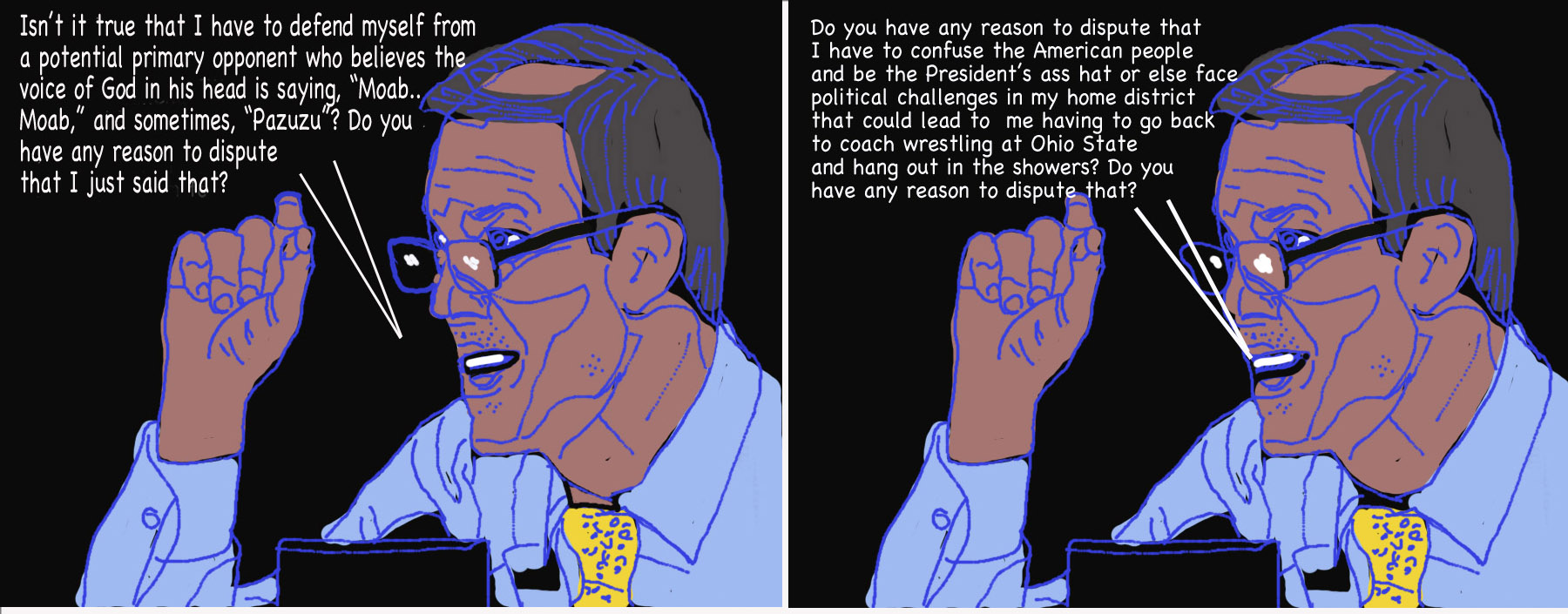

Follies Bér Comics

Play Drew's Quizzo and Win a Valuable Prize

Trivia is Important! Drew's Quizzo takes pursuers through a maze of facts and minutia that reveal his lifelong influences and obsessions. Click the drive-in marquee to get started!

ANSWER EVERY QUESTION AND WIN THE FAMOUS LAPTOP DRIVE-IN!

Art and Civics Dominate a Walking Tour of Philly's Downtown Public Sculptures

Our walking tour of prominent public sculpture around City Hall in Philadelphia begins with an exemplar of civic pride and industry. City Hall is the world's largest masonry building and has been called the epitome of the Second Empire architectural order. Intended to be the world's tallest structure when it was designed, by the time City Hall was completed after 30 years, it had been surpassed by the Eiffel Tower and the Washington Monument obelisk.

Called a massive boondoggle during the three decades of its construction, the largest city hall in America celebrated the history of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia, and boasted of the wealth of its merchant class. In 1870, Philadelphia was the largest municipality in the US, still the place where Benjamin Franklin in the early 1700s had journeyed from Boston seeking opportunity, and Centre Square, the site of the new municipal building, was on a public set-aside provided by William Penn himself in 1682. Rectitudinous capitalists like John Wanamaker believed in a government of the people that gave sensible businessman a free hand. The breathtaking spectacle of City Hall, decorated with fully articulated statues depicting Pennsylvania culture, is a celebration of the city that nurtured the success and fortune of its wealthiest citizens.

The marble, limestone, and granite building was designed by John McArthur Jr. and Thomas Ustick Walter, although the 250 separate sculptures adorning the structure were produced by Alexander Milne Calder. His masterpiece is the 37-foot-tall, bronze statue of Willam Penn atop the City Hall tower, the tallest such adornment in the world. William Penn weighs over 53,000 pounds, requiring crews of workers to hoist it to its pedestal in 14 sections. Calder wished the face of Penn to look south and stay in sunlight most of the time, but he is turned in perpetual shadow, facing Penn Treaty Park on the Delaware River, reputedly because the building contractor disliked the bronze behemoth or its sculptor.

Our tour would begin inauspiciously with stiff necks and strained vision if we were asked to peer high up on City Hall's façade to appreciate the details in Calder's modeling.  Fortunately, we are able to see small sculptures close-at-hand in the ground-level, north-south passage crossing under City Hall. A particular chamber along this passage has four different designs attached to keystones supporting the arches. They include a fierce lion, a heraldic owl, and an ordinary moo cow. Elsewhere on the façade, Calder depicts animals and plants native to Philadelphia, but the inclusion of the lion here suggests traditional iconography: these animals could be metaphors for strength, wisdom, and fertility, instead of a literal catalog of local fauna. In any case, our up-close look at City Hall's architectural details satisfies us as to their workmanship and vividness. The modern skyscraper eschews such ornamentation as dramatically covers every part of this building, and perhaps that and its lack of steel girders explains why to some visitors City Hall seems more antiquated than relevant a hundred and twenty years after its dedication. Hopefully the values of pride in place and civic duty it espouses still thrive in the present.

Fortunately, we are able to see small sculptures close-at-hand in the ground-level, north-south passage crossing under City Hall. A particular chamber along this passage has four different designs attached to keystones supporting the arches. They include a fierce lion, a heraldic owl, and an ordinary moo cow. Elsewhere on the façade, Calder depicts animals and plants native to Philadelphia, but the inclusion of the lion here suggests traditional iconography: these animals could be metaphors for strength, wisdom, and fertility, instead of a literal catalog of local fauna. In any case, our up-close look at City Hall's architectural details satisfies us as to their workmanship and vividness. The modern skyscraper eschews such ornamentation as dramatically covers every part of this building, and perhaps that and its lack of steel girders explains why to some visitors City Hall seems more antiquated than relevant a hundred and twenty years after its dedication. Hopefully the values of pride in place and civic duty it espouses still thrive in the present.

Going east along a courtyard passage to Market Street, on our left we find a monumental, eight-and-a-half foot statue of John Wanamaker, "Citizen," as its pedestal reads. Because statues of great men usually portray them in the ornate and complex costumes of long-past centuries, the sight of a bronze giant in an ordinary business suit can be disconcerting. The sculptor John Massey Rhind had only the features of Wanamaker's sagacious head poking out of a standard collar with which to establish a likeness; that, and he depicts this citizen as particularly well fed.

Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood Stacks Competing Story Genres

That new, epic poet in iambic pentameter everyone is reading describes how sometimes a generation contains so many overlaps of competing viewpoints and ideologies, a frustrated speaker resorts to irony to convey an utterance. Anonymous, perhaps you’ve heard of them, writes

For only rarely do words correspond

To the substance the writer based them on:

Speakers use them only because we must,

But never, ever are words worth full trust;

Consciousness of that gives us ironists,

Who stand two feet to left of what exists;

Both men and men's ages are prone to it,

The habit of speaking wryly and shit.

In the case of Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood (2019), the viewer understands wry  counter-meanings are beneath the surface because the discourse veers far west of conventions. Characters don't behave as they ought, or they espouse attitudes that make the audience cringe. Understood is the sly assertion of the writer or director that an absurd trope contrary to experience has a literary reality if not a practical one. In another grand Hollywood panorama, Boogie Nights (1997), for instance, the porn movie industry is the glamorized setting, an idea so naturally revolting and sordid in reality, that when we encounter it in cinema, we know the true meaning of the surface is displaced. Boogie Nights conveys the prosthetic extension of the 60s peace and love culture through a troop of x-rated movie makers, and it employs a recognizable Hollywood fairy tale to do it. The hip viewer gets it (a sense of humor helps), and soon we’re rooting for the hero, Dirk Diggler, same as we would if we were watching a shooting star in a Busby Berkeley musical.

counter-meanings are beneath the surface because the discourse veers far west of conventions. Characters don't behave as they ought, or they espouse attitudes that make the audience cringe. Understood is the sly assertion of the writer or director that an absurd trope contrary to experience has a literary reality if not a practical one. In another grand Hollywood panorama, Boogie Nights (1997), for instance, the porn movie industry is the glamorized setting, an idea so naturally revolting and sordid in reality, that when we encounter it in cinema, we know the true meaning of the surface is displaced. Boogie Nights conveys the prosthetic extension of the 60s peace and love culture through a troop of x-rated movie makers, and it employs a recognizable Hollywood fairy tale to do it. The hip viewer gets it (a sense of humor helps), and soon we’re rooting for the hero, Dirk Diggler, same as we would if we were watching a shooting star in a Busby Berkeley musical.

Tarantino’s movie is set in the 60s during the very events that many say killed hippie culture, peace and love: the 1969 SharonTate/Manson cult murders in the Hollywood Hills. Here again, the central characters are an extended group of moviemakers, especially a journeyman actor, Rick Dalton, and his stunt double, Cliff Booth. (The craft of Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt in these roles is beyond the scope of this essay, but let it be said that the conviction and integrity of the actors is another way the director can erase the disjoint between the mostly dispiriting topic of a TV western has-been and his equally laid low assistant and their place at the buzzing center of the audience's affections.) We are watching a movie about making movies, every phase of it, so we naturally peer through a smoky, not-as-it-seems lens the horse-opera exaggeration and alcoholic banality.

Meta-movies such as Richard Rush’s The Stunt Man (1980) make a game out of turning expectations on their head, resulting in works that declare the process of making movies to be ruthlessly anti-reality. A stunt man, we learn, is one of the members of the crew who best implements a movie’s disentanglement from physical and behavioral rules of conduct. (Coincidentally, the titular character in The Stunt Man was portrayed by Steve Railsback, who acted Charles Manson in the TV miniseries Helter Skelter (1976).) In the Tarantino work, Bounty Law actor Rick Dalton has two, real-life physical skills: firing a flame thrower and falling off a horse. For everything else, his stand-in Cliff takes the hit. By setting his film in the Hollywood milieu, the screenwriter signals the audience that the usual rules—-like a person having to be in one place at a time—-no longer apply in Tinseltown, and in this way prepares them for Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood's viscerally and dramatically shocking finale.

Tarantino incorporates another dominant fact about late-60s filmmaking into his tale. The old studio system is dying and a new era of independent films and actors takes hold. In the movie, Roman Polanski personifies the different kind of director, an artiste, not some studio hack. Along with the creative auteurs infusing the form comes  their new ways of looking at movie tropes. The conventional Western hero gives way to the anti-hero of the Spaghetti Western, exemplified by the character of Harmonica played by Charles Bronson in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). This anti-hero wears the duster of mystery, he’s cold-blooded and ungallant, not like Rick Dalton’s teeth-gleaming, preening bounty hunter in the NBC-TV oater, whose entire backstory is put across in the opening credits by a resonant narrator.

their new ways of looking at movie tropes. The conventional Western hero gives way to the anti-hero of the Spaghetti Western, exemplified by the character of Harmonica played by Charles Bronson in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). This anti-hero wears the duster of mystery, he’s cold-blooded and ungallant, not like Rick Dalton’s teeth-gleaming, preening bounty hunter in the NBC-TV oater, whose entire backstory is put across in the opening credits by a resonant narrator.

Tarantino imposes a throwaway, jarring narration for two brief segments. A stunt co-ordinator played by Kurt Russell voices some prosaic information about the Cliff and Rick partnership; hereby, Tarantino marks that strain of the story as existing in the world of the fake-y interview show that forms his movie’s opening scene. It has the un-ironic tone of a Disney wilderness documentary chasing after a cub, or a black and white TV commercial for cigarettes with a catchy jingle. Tarantino puts one of those featuring Rick Dalton at the close of the movie, after the credits, hyping the made-up brand Red Apple. Let me give it to you straight. It’s a smooth smoke. To some moviegoers Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood might play as a conventional buddy movie with weird extraneous flaws, but those apparent anti-conventions are intentional and convey the contrapuntal levels in the story, among them the tiny screen gems of the corporate establishment 60s compared to the freer, not formulaic movies that followed in the wake of the collapse of flower power and free love.

Artistic freedom is the raison d’être of new Hollywood. Corporate and by-the-book is the old style, thus Paul Revere and the Raiders are groovy, but Jim Morrison is far out. The Spaghetti Western, as Rick’s agent informs him, is a refuge for stars of the old regime who are past their leading-man prime in the corporate system. A refuge if they can act. Leone expanded the careers of Henry Fonda and Jason Robards because they delivered credible performances as murky criminals. Similarly, Tarantino has repurposed many actors from fondly remembered series TV in his multi-layered catalog. We don’t know about Rick. He lacks focus, and the hard life of cigarettes and booze is taking its toll. His story in the movie is whether he can still apply the acting craft exemplified by his eight-year-old co-star in Lancer, who must be addressed on the set by her character name “Trudy” at all times.

We see an imaginary screen test of Rick auditioning for the role of Captain Hilts, the Cooler King, in The Great Escape (1963). It’s Steve McQueen’s classic part, and in the screen test, which we know didn’t actually happen, in this movie or in "real" life, we are going to see the fantasy Rick, right, his ideal performance. We see it and--He’s...fine. Rick can beam those Hollywood choppers, but he can’t smolder, only smirk. Lacking the stillness of McQueen or Charles Bronson, he resorts to camp expressions and hollow intonations, never fully engaging with the character. Steve McQueen was tops, but he was still the old Hollywood; yet, compared to McQueen, we get side-by-side evidence for why the studios are leaving Rick Dalton in the past. Steve and Charlie made The Great Escape, and Rick got The 14 Fists of McCluskey.

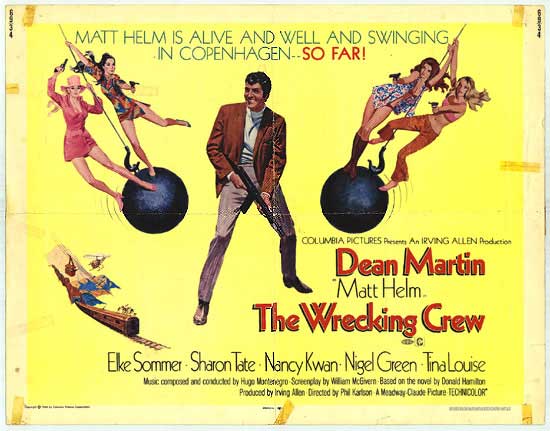

The cloaked anti-hero is so essential to the new cinema as the drink-in-hand smarminess of Matt Helm in The Wrecking Crew (1968) was essential to Dean Martin and his bosses on the Columbia lot. It's a movie from which two intact segments from the original are included in Tarantino's epic, the lunatic inclusions of a relentless pop culture addict. Dino's lurid ogling, effortless line reading, and phony action scenes don't play so well fifty years later, unless you're a child of the 60s, where all things spy-related were swoon-inducing, and Dino (only groovy, not far out) was the smoothest at half-singing double entendres to dreamy co-stars like Elke Sommer and Sharon Tate. In the same swinging style, Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood posts a segment of fictional Rick guest starring on the actual 60s pop music hits show, Hullabaloo, doing his smarmiest Dean Martin impersonation accompanied by a quartet of go-go-booted colleens. His fairly awful song is an extended double entendre, referring to the blue movie classic Behind the Green Door for yucks.

Tarantino presents the Swinging Sixties with the devotion of Andy Warhol. While dirty Hippies are derided in the film  explicitly and by implication, it is true the mainstream pop culture of Dean Martin, C.C. and Company, and Playboy Mansion was characterized by a swinging lifestyle distilled from the peace-and-free-love communism of the counterculture. In a huge Mansion party scene complete with ski slope-long tracking shots, Steve McQueen, Michelle Phillips, Mama Cass, and Sharon Tate drop by. Mini skirts shimmy. There’s Bunnies! Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood painstakingly recreates the music, style, and A-list of the late decade and undoubtedly the director is keenly nostalgic for them.

explicitly and by implication, it is true the mainstream pop culture of Dean Martin, C.C. and Company, and Playboy Mansion was characterized by a swinging lifestyle distilled from the peace-and-free-love communism of the counterculture. In a huge Mansion party scene complete with ski slope-long tracking shots, Steve McQueen, Michelle Phillips, Mama Cass, and Sharon Tate drop by. Mini skirts shimmy. There’s Bunnies! Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood painstakingly recreates the music, style, and A-list of the late decade and undoubtedly the director is keenly nostalgic for them.

Although it is often derided as a film trope by critics, the thing about nostalgia is that it recalls a time when Pop was experienced communally. The Green Hornet was a shared experience of kids all over the block, and always at the same Bat-Time, Bat-Station. No such central disseminator of cultural phenomena as the Hollywood factory for movies and television persists into the current century. Where is the capital of the Internet? We don’t even have record albums. Go to a Quizzo on a Tuesday in Philadelphia, and half of the questions are about songs and movies of which only a slim percentage of the barroom will have ever heard, and that includes the quizmaster. It’s pathetic.

Ironically, Tarantino’s nostalgia for the old days of the Hollywood formula is contrary to the postmodern cinema of which he is the foremost progenitor. He works a side of the street where meaning is turned upside down and conventional movie storytelling burned to the ground. Since there’s a form of power that harnesses the thermal contrast between the icy water at the bottom of the lake and the warm water at the top, it’s fair to say, Tarantino harnesses the differences between cinematic genres and powers his pictures with that. Styles and genres aren’t even available to the mind without thinking nostalgically; that is, unless one has the know-how to frame a proper Quizzo question, words like “Western,” “Disney,” and “buddy movie” are random gibberish.

The most pervasive trope in Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood is the fairy tale, the Disney version and the general Hollywood kind. Sharon Tate and her murder are central to this theme. At Cannes, Tarantino got heat from a reporter for not giving Margot Robbie’s character enough lines, and the director tersely refused to answer the question. His leading lady is literally barefoot and pregnant in this film. What was he going to say? The movie isn't about Sharon Tate as a physical person. She is a fairy princess, a movie starlet living the dream. It would be blasphemous to give ordinary human utterances to or guess at the sexuality of a legendary screen goddess. Tarantino is struck by the actor's goodness and incandescence. The ultimate fanboy, he gets to play with Columbia’s money and their film library. At a commercial showing of The Wrecking Crew, Sharon watches herself on the movie screen, bare feet dangling while closely attending the audience's favorable responses, a perfect starstruck ingenue. Tarantino doesn’t use the seductive dance Sharon does for Dean Martin's alter ego Matt Helm, but he does screen the actress falling on top of him. Double entendres ensue. In The Wrecking Crew, Tate is achingly beautiful; we hope nothing bad ever happens to her.

In the once-upon-a-time, Hollywood fairy tale, the good guys come to the rescue of a damsel in distress. Sergio Leone's movie features the same plot in a Western version. Tarantino's nod to his auteur predecessor contrives that authentic tough guy Cliff Booth happens to be in the Polanski “gate house” just as the Manson-family dragon invades. In the rousing fight scene that follows, we learn two important lessons: a well-trained dog is the responsibility of every dog owner, and three hours-a-day practicing your instrument is a good investment. The climactic showdown is right out of a grindhouse revenge shlocker. The Mansonites aren’t just killed, they’re exterminated, like the rats that flavor Brandy the pitbull’s dog food. It’s a revenge movie for something that hasn’t happened yet! The doubled prince saves the day, and he is invited by an angelic voice coming through a speaker up to the castle for drinks. Fairy tales are also transformation tales, and in this one, Rick Dalton, having transformed his acting career and slayed the dragon, passes through the guarded gates from the old Hollywood to the holy sanctuary of the new.

The substance of Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood is the friction between alternate styles and movie genres and irony is its pervasive tone. The buddy movie (including movies where a masked hero like the Lone Ranger or Cato has an ordinary alter ego) is one of the genres Quentin Tarantino mines to create a complex surface conveying an epic story, a “What If?” the 60s never died kind of thing. The complaint that it is revisionist, while literally true, is figuratively irrelevant. As we learned in 2019 from Avengers: Endgame, changing the past is impossible: history is indelible but with our high tech know-how and Hollywood sagacity we can alter our own present. “Do you guys just put quantum in front of everything?” Screenwriter Tarantino had an alternative technology at his disposal to revise the present by vividly transporting an audience to historic events. It’s called the past tense.

Drew Zimmerman, Aug. 2019

Self-Helpless

I have a page-a-day calendar that mocks me, which I keep for the perverse pleasure of it. The thing spews out positive thinking slogans commanding me to use

mind-over-matter willpower to accomplish my material goals. A friend got the offensive timekeeper through her office, and sloughed it off on me, because she knows I hate this sort of motivational device.

I deny on principal the efficacy of will or the power to impose consciousness on the physical world.

What's more, it is laughably vain to interpret features of the environment as signs of personal favor; however, since I couldn't get a free 1994 Ecclesiastes Verse-A-Day Calendar, every morning I take the earnest axioms of my self-help version with a strong dose of irony.

America has spawned any number of fawned-over prophets of self-improvement, the forefathers of my calendar, Franklins and Emersons who preach self-reliance and an unswerving adherence to a personal vision.

I would sooner consume a case of Nestle's Chocolate Diet Shake than slurp their humanist muck. For my dollar, the only domestic writer previous to Melville with the least idea of man's true relation to the cosmos is your

Jonathan Edwards. Hold up as a model some penny-pinching, beat-box marching, early-to-riser with a Jaguar, and I'll start screaming about the Fundamental Attribution Error. Jonathan Edwards shows you what the future really holds:

a sports car slipping over the rim of a black abyss and an eternity in the fire-y furnace.

Jonathan Edwards shows you what the future really holds:

a sports car slipping over the rim of a black abyss and an eternity in the fire-y furnace.

"Sinner in the Hands of an Angry God" exposes the error of relying on human faculties to gauge our safety on life's highway. Edwards is no blustering snake-handler: he has been to college and read his John Locke, but it quenches not one lick of hell's fire to accede to the well-reasoned premises of empiricism.

Sure, our senses reveal the world to us consistently and predictably, and from this data we make our plans and predictions. It seems so well-ordered and law-abiding and runs regular as a clock. Yet, despite all our experience of solid ground beneath our feet, we have nothing that may be counted as evidence

"that man is not on the very brink of eternity, and the next step will not be into another world" (Edwards 154). The laws we observe in the sensory world rely on crude induction. To place faith in them is to extract meaning from a marionette show without recognizing the strings. Reverend Edwards has read not only Locke but also Descartes.

The sensible world sustains Man because the arbitrary will of God commands it. Creation is indifferent to reason, especially man's notion of reason. The air would refuse to swell our lungs, Edwards writes, the rocks would not bear our weigth, and the Earth would not satisfy our hunger (157), except that God has stayed his hand against us.

The only law that applies in what the foolish Romantic calls Nature is the rule of God, and by that standard, we are already condemned. If it were not God's pleasure to delay our execution, this world whose coherence