Drew Zimmerman: Artist Statements

A radical axiom of B.F. Skinner’s Behaviorism observes that consciousness is rather inconsequential, that is, not formative of action. We don’t guide our hand to draw the arch of an eye with “mentalisms,” verbal commands. Instead, the body conceives and acts independently of consciousness, which swims along in the wake of things while taking credit for everything.I have found out the hard way that the average person has a fierce resistance to Skinner’s model of human behavior. (“Whaddya mean I didn’t tell myself to pour another cup of coffee?”) On the other hand, artists are particularly well-positioned to agree that the subject and style of their work comes from a non-verbal understanding of their materials, the incalculable muscle memories and ways of seeing and feeling that guide the hand to form the object.

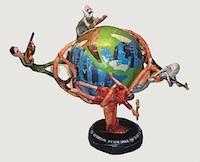

My art comes from paper-mâché in very specific ways. I can mumble and futz around with the ideas that informed the conception of an individual relief-collage or marionette, but the work originates in my life-long exploration of paper strips and paste: what they can do, the myriad forms cataloged in the muscles and recognized in the eye. When we speak about the hand of the artist, the unique signature of his or her interaction with a medium, description is plainly the vain attempt to communicate with words a purely existential phenomenon.

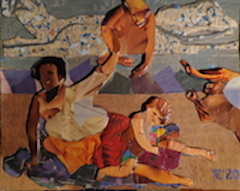

The hand of the artist–that ineffable trace of an individual life interacting with the material–to me is the salient production of every work of art. The expression of the mysterious interior life of one being to another justifies the heartache and pure drudgery of accumulating thousands of torn pieces of paper on a cardboard ground. I don’t care about resemblances; every representation is fundamentally an abstraction, whether a figure is the subject or some exercise of pure color and brushwork. A work is recommended by the way it communicates the indelible and deeply personal interaction of the artist with the grist of creation. Nothing else matters so much.

The art that remains is how we know here was a life and this is how it was lived.

(01/19/2022)

The techniques and themes of my body of work haven’t changed so much as I have refined and sharpened them. Since I began making art in 1980, my driving force has been the availability and versatility of my primary material, paper-mâché. Free of commercial paints and paintbrushes, bronze and the foundry; free to make virtually anything. I see myself, for instance, in the passion of Sam Doyle on St. Helene Island off the coast of South Carolina, commemorating his doctor by painting him on a repurposed medicine cabinet and Jackie Robinson on a 72-inch sheet of tin. Crude strips of paper and paste are so liberating as Archimedes' pulleys一 give me a place to stand and I can move the world.

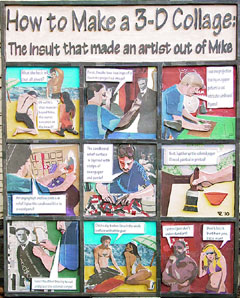

Although I have limited formal training in figurative representation, my knowledge of art as a subject is vast. “Folk art” seems to best describe my output. I use materials native to my environment, a comfortable suburb of Philadelphia, not the Georgia backwoods of superb vernacular artist Thornton Dial. My resources are recycled paper and cardboard, hardware-store steel wire, wallpaper paste, and, lately, Photoshop and a digital camera. (I also had an Etch A Sketch once.) I am a self-taught outsider, although, I doubt Jean Dubuffet would qualify what I do as Art Brut, as I’m neither naive nor insane. Nine years teaching English at Roxborough High is my version of Dial’s factory experience as a metalworker.

Early on, I made masks and marionettes because they had at least a modicum of practicality. My initial passion was marionette-building and performance, and I had a brief career as a street performer in Philadelphia in the early 80s. My partner just off South Street, “where all the hippies meet,” was my brother Lee. He later had a successful Hollywood career on live stages and television with a Jimi Hendrix marionette I helped him build and dozens of other marionettes he crafted using my basic, wire-frame design. Since then, I’ve made many videos featuring my facility for imitating all the departments of a movie production, using my own actors, scripts, and music.

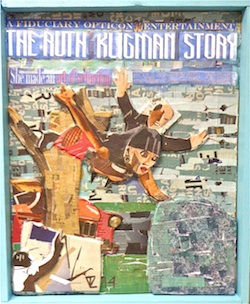

Almost immediately, I abandoned the use of paint to color the sculpture, turning instead to the application of torn paper strips of full-color, newsprint advertisements. My file cabinet contains 40 years of color ads gleaned from our local paper, which I call the Ink-Wire because of its usefulness to my craft. I started using layers of cardboard beneath the torn paper surface, achieving the element of relief in a lightweight, frame that hangs on the wall. Paper, cardboard, and glue–not stretched canvas– were my materials, and I wasn’t limited to portraiture on the flat. Besides the application of strips of newsprint, I used a home-made modeling pulp, the main ingredients of which are two egg cartons and two tablespoons of Elmer's Glue. Pound for pound, the commercial brand costs 40 bucks when they sell it at Michael’s, and pennies when I make it—plus mine is better.

In my most recent work, I’ve returned to the use of visual imagery to convey a story. My technical skill with video and software resources has evolved since my efforts in the 'Aughts decade. I still use paper-mâché to make backgrounds and puppets. In addition to marionettes, I’ve developed a Folk art version of stop-motion animation using wire-frame figures. Informed by the work of other visual artists (Joseph Cornell, Man Ray, Andy Warhol) who began as makers of a single image and later tried motion pictures, I have always had a certain disregard for the technical window dressing of professional filmmaking, because it wasn’t relevant to my practice. For instance, Warhol obviously cared more about assembling a film entourage than the final product. His subject was the star-making, taste-making function of publicity. My target is different, but spotting the microphone at the edge of my frame is irrelevant to it. As opposed to actual filmmaking, in which often new technology is the entire attraction, the only mechanical means I’ve ever owned that could beam an analog image on a wall was my boyhood toy, a Kenner’s Give-A-Show Projector. For me, Gerry and Sylvia Anderson's Supermarionation for Thunderbirds is more than dazzling enough.

Born into a gadget-mad era saturated with silly putties and play dough, I've worked through every kind of toy or summer camp craft that lets me shout the names of my heroes and curse the folly of my peers. Art degree? I have a degree in English and I've read its best practitioners, so, yeah, I know what art is; but, art school is about materials I don't use. The Pennsyvania Academy of Fine Arts shuttered its BFA program this year (2025), becoming exclusively a technical school after almost 100 years of offering the Humanities in addition to applying gloop with a paddle. Thanks anyway, but the winding spring of my creativity is identifying my human experience with other writers and a few iconoclastic artists, and if Spirograph were the only means I had to generate an illustration of my internal life, I would make do with it. Maybe my Folk art has been the art corollary to Rousseau’s pre-civilized man in his Natural state, a representation of the compulsion to create that is integral to the very notion of humanity. Or, maybe I like to make my own stuff.

(06/1/2025)