Apollodorus: A Dialogue

Leaving the old man on the stairs, I advance upon the library tower. I should feel more tired than I do, having wrassled Socrates and, before that, outrun the mob. Under the circumstances, the unlikelihood of my physical stamina–yet here it is!–means either I’m dead and just haven’t noticed it yet, or my Photoshop opacity is dialed down to zero.

My mind turns these questions inside and out. My father (your father?) had an electric car set in which he was exceptionally pleased, propelling those tiny magnetos at breakneck speed around and around a slotted track. My consciousness is a buzzing thing in constant motion, following the same old groove and getting nowhere. How shall I, one of literature’s flat characters, claim a will of my own? "Do not wait until fate leads you away from a man who says, ‘I know the answer to the question, “Is it destiny or is it free will?”’ but rather run screaming from him of your own volition.”

(I wonder if you caught what I did there, framing a saying inside a sentence not my own, conjuring a magical plasma of pure grammar, referring to a space that has never been known or occupied by a living soul in the history of man. And I’d like to know: what style of print or feature of punctuation would you use to indicate you are answering me?)

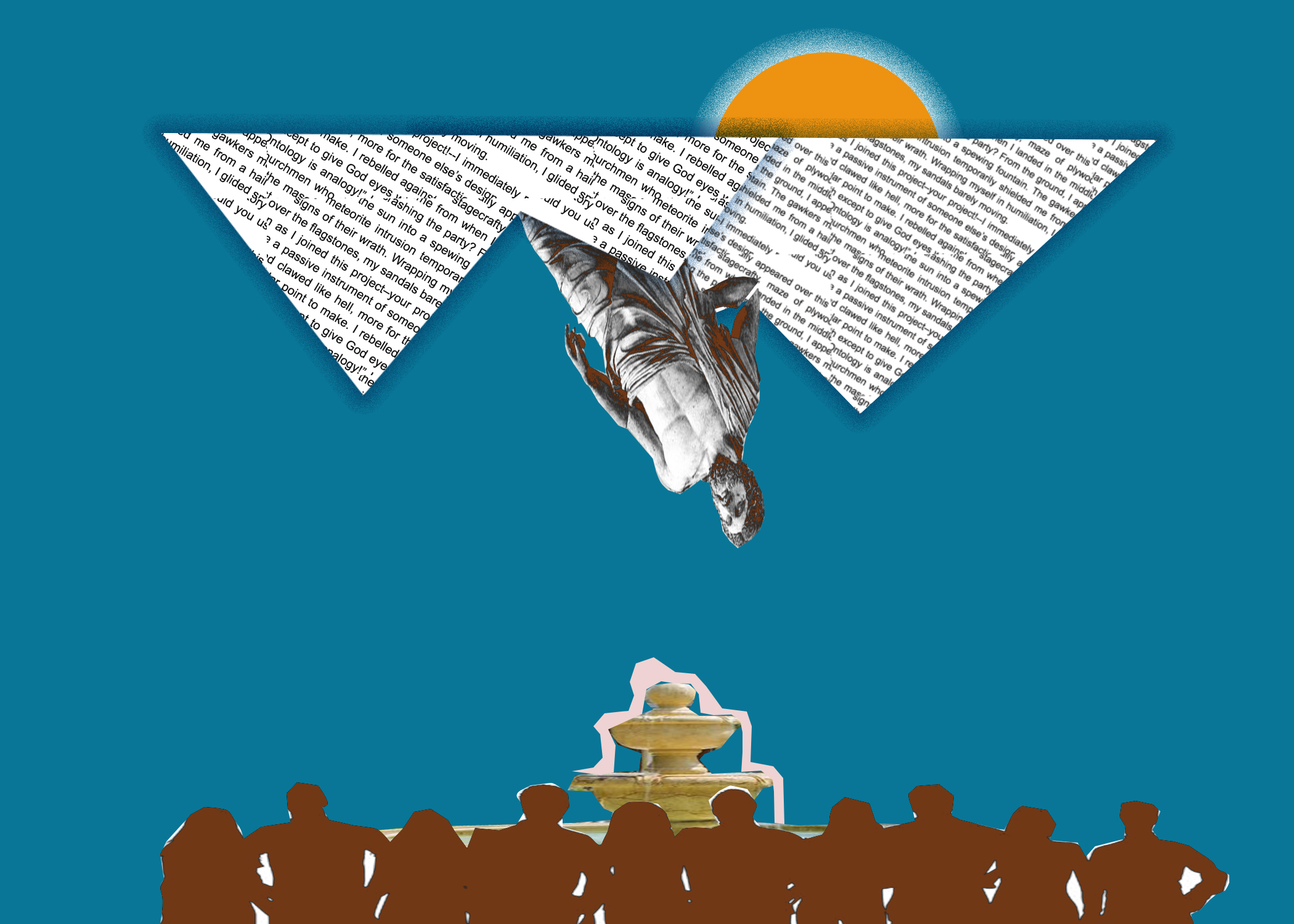

Did I have any choice when I magically appeared over this backlot version of Plato’s Republic, this embarrassingly stagecrafty maze of plywood facades and stretched canvas? Where had I come from when I landed in the middle of a wedding shindig in the Agora, literally crashing the party? From the ground, I appeared to have fallen out of the glare of the sun into a spewing fountain. The gawkers made a ring. Their wonder at my meteorite intrusion temporarily shielded me from a hail of sharp rocks and other signs of wrath. Wrapping myself in humiliation, I glided smooth as a skimboard over the flagstones, my sandals barely moving.

So soon as I joined this project–your project!--I immediately rebelled against it. That I should be a passive instrument of someone else’s design was repugnant to me, so I scratched and clawed like hell, more for the satisfaction of being a nuisance than for having a particular point to make. I rebelled against the forms! “Free will!” I shouted, for what am I on earth except to give God eyes with which to behold his own creation? “Oology is philology! Ontology is analogy!” I had to be free: free to praise and free to cower abjectly. Those churchmen who decided man’s liberty was a test of his fealty to holy law got it all wrong, the masochists. My existence revealed the weakness of my creator, not my own long list of flaws and self-defeating routines. Like the demiurge defamed by 18th century mystics, He couldn’t be the true “God,” infinite and omniscient, because He vainly sought his own reflection in the perception of man. Help! I’m the creation of a narcissist! Could anyone blame me for my belligerence and intractability?

Today, I marvel at how enthused I was with the prospect of personal freedom in my youth, considering that all the beatings and kicks I’ve received since then have taught me my freedom counts as nothing against my restricted choices. I was formed already possessing a fully detailed schema of the world; I didn’t have the opportunity to sculpt my reality out of the ether like a newborn. You cheated me out of the wonderous amnesia that blesses each infancy! Babies learn the geography and topography of home from others who will eventually share the same hallucination. They assemble from fragments of pure language the grids and streets of which the Republic is thrown together. And then they forget the whole process. Only an idiot could fail to suspect the greatest cover-up of all times!

Socrates taught that the forms of things exist separately from the way they are used in the market, public square, or human character. My understanding was coded into my sinews before I found the use of my limbs and senses. While a child’s real is a set of learned behaviors, my essence had been assigned to me before I came into being, fully formed like Athena from the insecurities of Zeus. Vomited into existence, I resented the ready-made city-state under my feet and in my nostrils as surely as the slave curses his irons.

My rebellion was a mirror of your own. To identify yourself as another of nature’s angry young men was the original reason for producing this document, wasn’t it? What had your roommate in the dormitory scribbled with a black Magic Marker by the pay phone in the hall, something about a genius of the bus queue, who believes he’s stumbled Joseph Lyell-like on an entirely original view of geological history and can’t stop himself from annoying everyone about it? You, standing on the bench bellowing, "Listen to me, everyone!" Bit needy i'n't?

Of course, your eagerness to move the tale along at a breathtaking pace to get to the part with the winsome priestess was the surest indicator of your youthful randiness and carnal obsessions. Looking as if her embrace contained the heavenly assurance of other lives beyond our own, Psyche was draped in the pure white chiton worn by space women on Star Trek, white as a dovecote, bleaching under the Aegean sun. Which famous painter was asked why he became an artist, and replied, “To meet girls.” Oh, that’s right! All of them.

In your youthful fever, you didn’t only transcribe a fantasy setting for your sexual longing. To be fair, you also expressed your rage against the oppression of the Platonic dystopia. The Republic advocates removing children from those least capable of raising them, their parents, and letting the state take over the crucial task of cultivating pursuers of justice, the greatest good. The Fantasyland to which you exiled me was governed by the ancient lie that every man’s nature was fixed, indelible as the destiny it foretold. Each man doing the thing for which he was equipped by the gods to do was Plato’s ideal. Sounds lovely until you find out someone else is going to take the measurements and assign the lockers.

You were twenty with half a bachelor’s degree from a liberal arts college: wasn’t your earnest critique in novel form of not-around-to-defend-himself Plato, if not exactly destined, then at least predictable? Too bad you left campus too soon to hear the critical bombshell that The Republic is satirical: the reader is supposed to think its exercise of pure rationality exceeds what is possible (even if it’s probably a good idea). I’m sure the reasons you dropped out of the English degree program–that no one can teach writing and no one needs to know physical geography or French–were valid. Behold the success of your non-conforming strategy! I, your scruffy protagonist, am the only reader who followed this story from cover to cover, and even I am mostly fuzzy on the details.

Considering the nearly total obscurity of your creation, doubly wondrous was the specially delivered message sent to your doorstep one chilly dawn forty-five years later, an official demand that you “account” for your contribution to literature, a book with only twenty known copies, distributed to friends who didn’t read it but thought it was “nice.” Government in your own time and place being even more overbearing than in Plato’s dystopia, your heart sank; a chasm yawned before you. In some deep cabinet along with a sixth grade report card and a ragged photograph, had you even saved a copy of the manuscript? What was in the work those newly installed, extremely attentive, homeland security-type readers might find critical? And where, by the way, was the New American gulag? Michigan’s Northern Peninsula? the Great Salt Lake?

I always liked the title of this exercise: Apollodorus: a Dialogue. You found a character mentioned more than once among the minor players in Plato, a follower of Socrates who is described as being a bit dim, maybe even half-mad, but loyal. One night in campus housing, you were struck by a thunderbolt: write a story that fills out the brief sketch provided by antiquity and results in a climactic showdown between Socrates and his Number One Fan. The idea seemed to you in all its jewel-like perfection so brilliant, you were actually paranoid that someone would write it before you did, as if the public in the late 20th century was clamoring for all things of a purely philosophical nature and literally older than God. Move over Alfred, Lord Whitehead! Time to squeeze another volume into the Harvard Five-Foot Shelf of Books! Besides being a dialogue in the Platonic sense, a debate between sophists with different wacky opinions, you conceived a book with an unwilling main character, straining under the yoke, kicking over the traces, and cursing his maker from the pages of the story. The profanity-laced speeches of the character in the novel conducted an angry dialogue with the contrivances of a plot and his pre-engineered utility to it.

I admit in regards to my female co-star in this tale I was perhaps less angry, less put upon than was appropriate to my spiteful characterization. She was named for Psyche, the mythic embodiment of the soul who was the original doomed bride in Beauty and the Beast, a woman so beautiful she was worshiped by men and an insult to Aphrodite. The goddess sends her son Cupid to prick her with his poison arrows and force her to fall in love with a monster. Instead, it is Cupid who becomes hideous and inhuman: cut by his own dart, he falls in love with the maiden and hides his true sexual nature in the dark, ashamed of the carnal passion that is wreck and ruin to the jewel of maidenhood and a discredit to his own immortality.

The Psyche in our story was a priestess of the Temple of Love, trapped by the worshipful desire of her scores of suitors, which prevented her from choosing any one of them as a husband so she should remain the idol of them all. I dropped in, uncouth and profane, a trampler of shrines and sworn deflowerer of virgins. Psyche liked me right away. “No more flowers! What shall we throw in next, monster?”

The myth of Psyche and Cupid, the dance of erotic love and the indelible soul so difficult to untangle, has a Jungian interpretation and a feminist one, but I don’t care about either of those: I’m not interested in literary interpretation. The wonder of my darling is how I was made to love her. Our beings were cosmically entangled, like those quantum particles physicists tell us do that yin and yang thing separated across galaxies. You would know better than I what unanswered question in your fixed past created the possibility of redemption in my streaming present. How could I not pursue Psyche, embodiment of soul, I who was created without one, an engraving on a marble surface lacking any interiority? Cupid unknown, hiding in the dark, is a monster of carnal desire; restoration to his godly form, if not salvation itself, comes from being seen and recognized by a worthy Other.

I have attained the door to the library tower, a massive, bronze-cast barrier, adorned with panels of figures in relief. At the top, the traditional caricature of Homer gestures a benediction. The relief work narrates some hero’s journey. If I wanted to figure out which one, my usual method would be to first identify the monster. I hear the mob in pursuit, seeking justice for my blasphemous travesties against Aphrodite in the form of violating the sacred person of her priestess. Another faction wants to stone me for inciting insurrection against the Republic.

Plotwise, you threw me in with the rabble who live beyond the walls of the city-state, its laborers and tradesmen. In a fiction set in a mythical world, where men are raised up on pedestals for their skill at sophistry, I earned my bread and shelter giving speeches expressing the plight of the downcast, whose opportunities the state confines to a narrow band. Why must it be that society, despite its chest-thumping to the contrary, despises sweat-of-the-brow work and exalts everyone with a confidence scheme to avoid it? Asking questions such as this one, I made enemies of the ruling Council of Twelve (because there's always a Council of Twelve). By narrating my turn at rousing the rabble, you earned an audit from a nascent totalitarian regime hiding inside their own boardrooms and bureaucracy. How these pages attracted their notice, we’ll never know, but you were told to prepare an account of yourself and present it to men with clipboards, ten thousand-volt prods, and secret account numbers.

To my surprise (What the..?) the massive bronze door to the library pushes inward without so much as a guard at-hand to prevent my entrance. I had prepared myself to wait just inside the portico for some taciturn, robed official whose sole reason for existence was to deny me access. How I would bribe and cajole him to let me pass but to no avail: „Diese Tür wurde nur für dich geschaffen, und jetzt schließt sie sich für immer!“ I glance over my shoulder and see the flickering light of the mob’s torches casting huge shadows on a wall opposite. I see Socrates on the stairs below, rocking back and forth with his head in his hands. No doubt, he will recover, but my fate is less certain. I duck inside the building and enter the spiral stair ascending the library’s masonry tower.

Less than an hour ago, Psyche and I held each other close. For a week–the span of the novel–we had been sneaking around, contriving to get a few moments of privacy. In my opinion, our scenes together could have been more explicit, but I get it. No need to get “arty.” Even with most of the physical contact between us being more or less a matter of inference, she made her mark on me. We kissed in the tunnel that passes under the walls of the town. Her scorned suitors and keepers of the civic order clamored in their approach. I said, “Goodbye!” and “I will always love you!” and took to my heels.

Psyche and Cupid is a Roman myth, not Greek, and it was one of the last to be put into writing. Does that mean the idea of a human soul is a relatively late invention? Had language made the leap from vocal speech to the noise in our head at about the same time? Remember that the conventions of poetry, theater, the novel, and biography were all contrived by humans, not handed down to us from Mt. Olympus. Writers discovered the means in the toolbox of grammar to present separate events as causes and effects and individual human behaviors as springing from a dependable nature.

The ancients had different words for sexual love and the true love between persons that expresses their mutual admiration for traits of creativity, a finely tuned reason, and the refinement of muscles and manners. Failing to make a distinction between eros, philia, and agape, smashing them into a single concept, domesticates the feeling between sympathetic actors, tying it to family, inheritances, younger people that look like us, and a whole sluice of mundanities. Ultimately, we all benefit from the awareness that the notations available in our language to express the human experience are in continual flux. How much is what we feel about others or project onto a mythical soul a feature of language, replete with words that have lost meanings, obscure origins, and connotations that become obsolete from one generation to the next?

Freud based some of his myth-writing about the human psyche on the biological principal ontogeny repeats phylogeny, which in his mind rationalized the idea that the development of an individual mind recapitulates the development of the whole culture. What individual consciousness has not passed in a lifetime from anxiety over what is coming to the satisfaction of realizing its whole history is written? Will such a maturation of perspective come to the macrocosm? Can political jockeying, in which team red and team blue constantly trade hegemony, eventually give way to a wise acceptance of the end of regime change for eternity? The culmination of history tosses out all ledgers, and the cosmic game of musical chairs lasts only so long as someone puts quarters in the jukebox.

Since I held, for a moment, Aphrodite’s priestess in my arms and released her to the ages, it seems to me the cellular structure of this story has metamorphosed. Our dialogue began as the angry protestations of a callow, self-proclaimed author, self-conscious of how his words would be received by a future full of readers. That college kid never gave a thought to how his words would be understood by his future self, rereading his freshman novel as a wrinkled senior, searching for connections between a shiny penny and a tarnished one (we can’t see it or count it, but their value is identical). You’ve been asked to “account” for yourself by a nameless external entity, and what does that even mean? “You’re an accountant, Bloom; account for yourself!” Whatever its dimension as a work of literture, a memoir conceived in the uncertainty of youth is a priceless boon when revisited by its now old and bone-weary author.

Peeling away from the printed page in metaphor if not reality, I have been a character ranting against his creator, calling the abstraction of your life through a paper narrative a cowardly kind of abdication. Yet now, as the story reaches its conclusion, I find against expectation that my feelings have mellowed. First of all, Psyche’s full-armed embrace smoothed my outraged brow, bestowing a comfort within my own skin that I have never known, a consciousness that dates back at least several paragraphs.

Winning the blessing of the woman of your dreams makes a difference, but so does the demonstrable, historical fact of Apollodorus, which has absolutely nothing to do with its aesthetic dimension. Factors like its stilted tone and one-dimensional characters that argued against it in the last century don’t seem consequential, today. Maybe, what reads like poor writing is actually brilliant isopsephy: start counting. Far from being proof of your ineptitude as a novelist, the anonymity of your accomplishment recommends it. Had you a readership of five million, their effect on you personally would be no greater than if your readers were four or five. What is amazing is that you constructed a narrative out of a primordial ooze unable to organize itself into anything more than a fist. From my vantage on the trailing edge of that story, I find the effort charming, and in any case, I’m not angry any more.

Saying farewell to my beloved, I had no remorse. I was acquiesced to my fate; the shape of my story was a mystery no longer. Next in the narrative, what had been written 45 years ago as the fateful showdown between your protagonist and Plato’s alter ego, stout, snub-nosed Socrates, was no longer the mugging of outmoded old age by angry youth you originally intended. I traced the outlines of my actions and said the same speeches, but they signified something different in twilight than they meant in the dawn of the plan. Instead of an ambush, we shared a sort of commiseration.

Socrates saw me in the square, read the look in my eyes and discerned their laser focus. I called out to him, and he ran in the opposite direction. Fate, not cloaked in the raiment of Lachesis and Atropos but in the equally unalterable form of the historical record, was not easily escaped. I tackled my old mentor to the hardscaping, sat upon the overhanging duffel of his middle-aged sprawl, and pinned his arms to the ground.

“I beg your pardon, master, but I must have answers! You claim the physical world is not so timeless or absolute as the forms of which these figures in the landscape are mere shadows. I have no knowledge of the eternal truth of the Good or Justice or any of those abstractions! My temper is that of one who is shipwrecked, unmoored as I am from the harmonious order of reality.”

“Help me, someone! He’s a madman!”

“Yes! I’m insane! Leastways, I see not with clarity the Good ahead of me, the Good that will result from present actions, nor do I see the fine, strong threads of Reason but only the manipulations of clumsy language figments with no parallel in reality.”

“Please, Apollodorus, whom I once loved as a disciple and friend! Release me from your..(unh).. malicious..(ungh).. snares!”

“Demonstrate to me the eternal order of the absolute forms of which you speak or, no, I will not let you go!”

“Somebody, help! Ouch! Ach! He’s hurting me.”

Recalling the social preambles that introduce Socrates’ proform oratory, I demanded, “Whom do you mean when you say ‘he’ is hurting ‘me’? For aren’t these relative terms, dependent on specific syntactic settings? Isn’t the notion of an individual Apollodorus, acting autonomously from the plentiful pulleys and levers on his behavior, absurd prima facie since the premise requires us to believe one lowly, earthbound creature, requiring regular breaths of air, loaves of bread, and gulps of water, could independently execute an action of the kind you mention? And my question puts to the side completely the teaching of Parmenides, who demonstrated that action itself is impossible, depending as it does on the coordination of causes and effects which, in a monastic universe where everything that is is indivisible, is logically absurd.”

“Won’t somebody please get this madman off of me?”

I spoke my peace to Socrates and a few pieces more, getting no answers and expecting none, then hurried to the library tower. One time, outside the city’s walls (the underground resistance passes in and out through a secret tunnel), I met a man sitting quietly with his back against a wall. I had been performing feats of elocution all morning and paused to ask him did he subscribe to Socrates’ view of Justice.

He squinted at me, hardly lifting his head. “The Greeks conquered a people centuries ago who had no nouns in their language, only verbs. They described everything as an action. In that language, Socrates doesn’t even exist.”

Tarot’s Major Arcana carries on its spokes a tower being struck by lightning, representing an upheaval or change. To an old man watching himself transform from his youth in real time, the symbolism was apt. Once I resented being put into words and would have destroyed Plato’s Republic had that been my story to tell. In the end, I seemed to be the only character in a story about an old man, and some solace I found in that. The world had changed and suddenly an obscure manuscript had intent readers, searching for hidden meanings, and is that not the dream of every author? When I fell asleep in the 1970s, I still lived in a democracy. Decades later, I woke up in a country so similar to Plato’s Republic my pretentious novel became, well, portentous. Scholars may one day describe what I have done with the same comic flair as they name the various maneuvers of competitive figure skaters: you could call this one a Double Reverse Winkle!

In a world where deformity and aberration are the norm, Plato’s work doesn't succeed as satire, and anyways, I wasn’t made to fire my bolt against symbols of power. “I’m here to declare myself above every vagary and vanity under the rising sun. With a story that is immutable between its covers, I’m checking myself into the library.” And somewhere a Greek chorus performs an apostrophe.

–-Drew Zimmerman, 2022