In Crafting Narratives, Art is the Abstraction of Everyday Use

In a 1956 interview on NBC-TV, Marcel Duchamp describes the dramatic moment his work as a conventional artist changed course irrevocably. He had been painting in the manner of Impressionism because it was the official style of the only fine arts education available during Duchamp’s youth. By the end of the first decade of the 1900s, Duchamp determined that he wouldn’t paint any longer blindly following immediate public taste; he would, from then on, paint only what pleased and interested himself. To reinforce the notion, he got a day job in a library so as not to be dependent on painting to earn his daily bread.

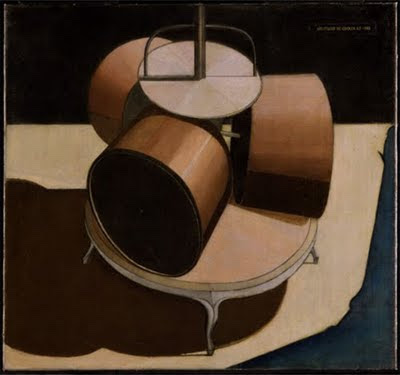

The first work produced by the newly liberated artist made a chocolate grinder its subject, thereby elevating a craft implement to a position of art. Duchamp tells James Johnson Sweeney, director of the Guggenheim Museum, that he became delighted by the motif of a chocolate grinder when he came upon an actual mechanical one in a chocolatier’s window. It was critical that the machine had been pulled out of its useful place in the mass production of candy and put before the public as the emblem of the chocolate shop’s virtue. The repurposing of the industrial machine was visually logical in the era that was experimenting with Cubism and abstraction. The cluster of metallic drums spawned by the necessities of the grinding process had the unexpected characteristic of being aesthetically pleasing. Also, Duchamp was amused by the verbal and visual sexual punning suggested by the device.

that he became delighted by the motif of a chocolate grinder when he came upon an actual mechanical one in a chocolatier’s window. It was critical that the machine had been pulled out of its useful place in the mass production of candy and put before the public as the emblem of the chocolate shop’s virtue. The repurposing of the industrial machine was visually logical in the era that was experimenting with Cubism and abstraction. The cluster of metallic drums spawned by the necessities of the grinding process had the unexpected characteristic of being aesthetically pleasing. Also, Duchamp was amused by the verbal and visual sexual punning suggested by the device.

He would paint the chocolate grinder’s form twice in what he describes as a “mechanical” style, and later deploy it as a dysfunctional reproductive organ in the mixed media The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass). The artist recognized that industrial processes, born of pure practicality, created independent of artistic intention a kind of “ready-made” art, abstract sculptures with a pleasing form divorced from their chocolate-grinding, bottle-drying, bird-caging, or excretory functions. At the start of the Twentieth Century, Duchamp embraced the industrialization of common life as being in harmony with the long processes of history, rather than subject to the short-lived whims of popular taste. Wanting to be an artist of his time, he tells Sweeney, Duchamp utilized the mechanical style of rendering three dimensions and incorporated mass-produced forms in his creations.

The impulse to take everyday materials associated with practical work and use them to make works of art is central to the show "Crafting Narratives," on display in Philadelphia’s Art in City Hall space until New Year’s Eve, 2019. Shaving distinctions between craft and art is a parlor-room pastime of dubious value; however, art is the logical successor to craft whatever else we attempt to say about it. Metalworking, paper-making, weaving, painting, pottery--all craft traditions begin as the manufacture of practical goods for everyday purposes. Using that same accumulated knowledge of the material and the forms into which it can be worked, artists break with craft tradition by creating objects that have no value as furniture, arrowheads, boxes, blankets, or other tools. Instead, art un-empirically consoles the human psyche, most basically as a means of commemorating human events, personal and public.

on display in Philadelphia’s Art in City Hall space until New Year’s Eve, 2019. Shaving distinctions between craft and art is a parlor-room pastime of dubious value; however, art is the logical successor to craft whatever else we attempt to say about it. Metalworking, paper-making, weaving, painting, pottery--all craft traditions begin as the manufacture of practical goods for everyday purposes. Using that same accumulated knowledge of the material and the forms into which it can be worked, artists break with craft tradition by creating objects that have no value as furniture, arrowheads, boxes, blankets, or other tools. Instead, art un-empirically consoles the human psyche, most basically as a means of commemorating human events, personal and public.

The subject of making aids to memory characterizes metalsmith Patricia Sullivan’s Portrait of Woman in Twelve-sided Frame, Sullivan enshrines tiny photographs of a woman and her environs in lockets of metalwork, a classic form, so old as photography or locks of hair. In her blog, she acknowledges another subject at play here is the dimensional similarity between lockets and the digital widgets that distinguish our accounts on social media, those tiny photos that if you click on them, link the face of the person contributing to a discourse with their biographical information and full history. Conceived as a precursor of the digital emblem that makes identity also a brand, Sullivan’s lockets depart from craft itself and think artfully about what constitutes a memory and what solace we might seek from it.

Beyond the practicality of chains and chambers is the immaterial pleasure of safeguarding an image of the beloved, and beyond that Sullivan finds a second level of abstraction. Portrait of Woman in Twelve-Sided Frame metacognitively explores what a portrait is for, while shrinking from objectifying more than an abstraction of a particular woman. Carefully preserved pictures include a lady obscured behind her hair and hand, and a nondescript rowhouse of routine red brick. Unless one already possesses intimate knowledge of the person and place in the photographs, they reveal very little, but a practical portrait is beside the point: like Duchamp’s ready-mades, Sullivan’s Portrait defines a border between manufactured products and the mysterious subset of craft we call “art.”

While Patricia Sullivan repurposes the age-old craft of metalsmithing to a personal, artistic purpose,

Named for the Conrad novella that probes European colonialism and the conception of the “primitive” in the minds of those who exploited African people, Heart of Darkness is physically an overturned chest, wrapped with twine and decorated with ribbons, a bottle, machine-worked wood, and torn pieces of black and white photos. It resembles a dark cotton bale, but the photos arranged on the top are like growing stories from black soil. Broken objects here are repurposed as a memorial to the resourcefulness of a subjugated people; someone has strung bright red and green beads along the razor wire.

Daniella Siegelbaum’s playful Mask of the Sea Sick treats cultural symbols from around the globe as flotsam and jetsam, and organizes them in a woodworked, tribal mask. A goggle-eyed spirit with an ebony horn catches green-scaled fish and Arabic numerals on metal hooks. The piece is strung with many colored, wooden beads, the use of machined decorative baubles as decorations being one of the craft contexts in which Siegelbaum’s mask resides.

Whether borrowing materials from the modern environment or mining our deep resources for encountering information about other times and places, artists in “Crafting Narratives” repeat Marcel Duchamp’s penchant for elevating random encounters to the level of high art. The narrative in Atlas (Drew Zimmerman, 2010), comprised of nine frames in cartoon form, refers to an advertisement that appeared in comic books all through the artist’s mid-60s childhood. In it, a 98-pound weakling overcomes his oppressive environment by subscribing to Charles Atlas’ bodybuilding program. “The insult that made a man out of Mike” was the ad’s tagline.

In its repurposing of a mythic mass-media artifact, Atlasspeaks of the rejuvenating powers of art, how the artist is empowered by relating his narrative. The four-by-five-foot relief collage breaks down the process by which trash newspaper and cardboard are rescued and transformed into a colorful portrait. Rarely used in mainstream art, paper mâché is, nevertheless, a perfect folk medium, and Atlas' hyper-consciousness of the materials that composed it recalls the discipline of craft. In a tongue-in-cheek way, the “painting about painting” doctrine of Abstract Expressionism is also evoked, but unlike the work of De Kooning, for instance, full disclosure of process in Atlas paradoxically obfuscates its true content, which has more to do with the insecurities of the marginal artisté. “Who’s holding up the world?”

Against all reason, an artist longs to be useful, necessary to the day-to-day realities of society; however, by its basic impulse--Duchamp’s resolute turn away from the chocolatier’s window-- art disqualifies itself from that which it most admires. Consider the expertise with which Elizabeth Coffey-Williams utilizes the essential

A much anthologized short story by Alice Walker, “Everday Use,” explores the complexity of the relationship between practical craft and art. An urbane woman returns to her mama’s farm to rescue an heirloom quilt from being something one sleeps under and enshrine it in her city house as a work of art. Her view is that her mother disrespects African-American heritage by subjecting such an object to everyday use; Mama believes she honors her ancestry by practicing the craft of quilting and feels closer to her deceased relatives when using the blanket she inherited. Walker’s story tilts towards the latter argument, which is ironic since the Pulitzer Prize-winning author, of course, is herself a celebrated artist. It’s an argument that can never be resolved: what is more useful, a prosaic comfort against the hardships of the physical world, or art, which can’t possibly provide a livelihood, but comforts the spirit? As Duchamp tells us in his televised narrative, for good or for mischief, the artistic impulse begins with abstracting the materials of practical craft.

©Drew Zimmerman, 2024